Computer Chronicles Revisited 1 — The HP-150 Touchscreen

The Computer Chronicles debuted as a national television program in the United States in the fall of 1983. The series was the brainchild of Stewart Cheifet, then the general manager at KCSM-TV, a public television station based in San Mateo, California, which was in the heart of Silicon Valley. Cheifet originally launched Chronicles as a live, local program in 1981 was hosted by Jim Warren, the co-founder of the West Coast Computer Faire, an annual computer industry show held in San Francisco.

Cheifet told Leo Laporte in a 2013 interview that Warren’s local show–intended to be a televised computer user group–went viral before the term “viral” existed. Other PBS stations around the country started calling Cheifet asking if they could carry the show. Eventually, Cheifet decided to relaunch The Computer Chronicles as a taped program with himself as the host and went looking for underwriters.

One potential sponsor Cheifet spoke with was Gary Kildall, the founder of Digital Research, Inc., which developed the CP/M operating system. Not only was Kildall “totally supportive” of the idea, Cheifet told Laporte, but he offered to co-host the program. Cheifet noted that Kildall was an experienced pilot and often flew his private plane from DRI’s hometown of Monterey, California, to San Mateo each Saturday to record.

The Computer Chronicles went on to run for two decades, from 1984 until 2003. Cheifet served as principal host for the entire run and later created a companion program, Net Cafe, which focused on the growth of the Internet during the 1990s. Kildall would continue as co-host of Chronicles, with intermittent absences, until 1990.

What Was The Computer Chronicles?

The Computer Chronicles was a newsmagazine-style program. Each show typically began with a brief host segment where Cheifet and Kildall would introduce the subject for the week. This led into a pre-recorded feature narrated by Cheifet in the first season and a beat reporter in susbequent seasons. There were then between one and four segments involving either a product demonstration or a roundtable discussion. Typically, a manager or developer from a given company would talk to Cheifet and Kildall in-studio and show off their latest project, which related back to the subject of the week.

At the end of each program, there was a straight news segment offering roundup of weekly technology-related stories called “Random Access,” again presented by either Cheifet or another journalist. This segment would also often feature a brief software review presented by technology journalist Paul E. Schindler, Jr.

A Nostalgic Look Back at Computing History…in 1983

The subject of the first nationally broadcast episode was “Mainframes to Minis to Micros.” Cheifet opened the host segment by asking Kildall, presumably with tongue firmly planted in cheek, if he thought we were “at the end of the line” with respect to the evolution of computers. Obviously, Kildall replied no, pointing to the new trend of using microprocessors as general purpose computers. He said eventually, computers would get so small you would “lose them like your keys.” He even saw microprocessors being used as controllers for non-computing devices such as wheelchairs.

This led into the episode’s pre-recorded feature, where Cheifet narrated an introduction to the Computer Museum of Boston, a nonprofit organization that housed a collection of many early computers and calculating devices, such as the TX-0, the Pascaline, the Illiac IV, and the Whirlwind I.

The feature continued into a second segment, which included snippets from an interview with C. Gordon Bell, a member of the Museum’s board of directors and a former vice president at Digital Equipment Corporation, where he worked on the TX-0. The segment then transitioned back to the studio, where Cheifet and Kildall spoke with Herbert Lechner, vice president for information systems and administration at SRI International, a nonprofit scientific research institute originally founded by Stanford University. Cheiefet asked Lechner if he believed that microcomputers–i.e., personal computers–would take over from the minicomputers produced during the 1970s. Lechner replied that he expected to see a wide range of high-end and low-end computers on the market. He pointed out that software would play a key role in the ongoing evolution of hardware. Kildall noted that smaller systems emphasized “real-time control” by the user rather than the time-sharing common with larger mainframes.

Lechner and Kildall also commiserated over the rapid changes seen in the computer industry during the past 30 years. Lechner noted he was part of the team that developed the IBM 702 mainframe back in the 1950s. At the time, Lechner said it took a team of 17 people working for nearly a year to install the 702–and they wondered then if they could even sell 30 such systems in the entire United States.

It’s Like a Rolodex…But on a Computer!

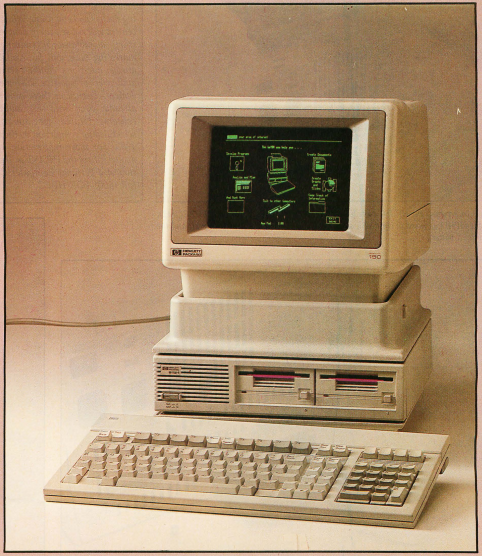

The final segment of this first episode was also the first-ever product demonstration. Cyril Yansouni joined Cheifet, Kildall, and Lechner to show off the HP-150 personal computer. Yansouni was general manager of H-P’s personal computer group. The main selling point of the HP-150 was its interactive touchscreen. As Yansouni noted, touchscreens were not an entirely new technology. They had been used on terminals. But what H-P offered was a machine that embedded the touchscreen’s functionality within software applications.

Yansouni demonstrated an “electronic Rolodex” program where the user could use the touchscreen to manually scroll through virtual contact cards. He showed how you could print out an individual card using the HP 150’s built-in printer. Alternatively, if a modem was attached, the user could touch a phone number to initiate a call.

Kildall said that one criticism of touchscreen-based interfaces was that holding up a finger all the time can be tiring for the user. He joked that H-P might want to offer an armrest attachment. Yansouni acknowledged that the “ideal” user interface had not yet been developed. He said further experimentation was necessary, and that in the future we would likely see a combination of things, including mouse-based input and voice, that could be used with a specific application.

Cheifet then pointed to yet another “new” feature of the HP-150–disk drives that supported microfloppies, i.e., 3.5-inch diskettes as opposed to the industry standard 5.25-inch disks. Yansouni said HP’s microfloppies had the same density and storage capacity as 5.25-inch disks, and over the next several months he anticipated an improvement in microfloppy capacity up to 1MB.

The segment, and the show, ended with a brief colloquy over the likely “next step” in computer evolution. Lechner said one trend to keep an eye on was networking computers together, both in the form of local area networks (LANs) and over telephone lines. Kildall said he expected most of the advancement in this area would involve the latter, as LANs were expensive and had a lot of problems, while telephone-based networking could rely on existing infrastructure. Yansouni agreed with Kildall, adding that telephone-based computer networking could help promote the use of voice interfaces.

Touch the Screen! Touch the Screen!

(Editor’s Note: This section was added in November 2023 and adapted from Episode 14 of Chronicles Revisited Podcast.)

Hewlett-Packard was one of the original Silicon Valley companies. Founded in 1939 by Stanford-trained engineers Bill Hewlett and David Packard in a Palo Alto garage, H-P built its reputation developing electrical instruments and serving as a military contractor during World War II. By the 1960s, H-P had diversified into a number of areas including computing. H-P’s first mini-computer, the 2116-A, debuted in 1966, although the company described it to the press as an “instrumentation controller.” David Packard later said he refused to call the 2116 a “computer” because that would imply the company was in direct competition with IBM, who was not only the dominant computer company in the country but also an important HP customer.

But a computer by any other name was still a computer. And in 1972, H-P followed up on the 2116 by launching the HP 3000 line of mini-computers, which proved so successful they were officially supported well into the early 2000s. That said, H-P was not an early entrant into the micro-computer market when it started to take shape towards the end of the 1970s. In 1976, H-P management famously declined to develop a micro-computer prototype created by one of its engineering interns, Steve Wozniak, who later turned it into the Apple I.

But by the start of the 1980s, Hewlett-Packard realized it was behind the ball in not having something available for the growing business micro-computer market. So in 1981, the company launched its 100 series of personal computers. The first machine in the series, the HP-125, was based on two Zilog Z-80 micro-processors, came standard with 64 kilobytes of RAM, and used Gary Kildall’s CP/M operating system. The 125 also had an integrated monitor that used the same housing as H-P’s dumb terminals. A year later, in 1982, H-P released the HP-120, which was effectively a smaller version of the 125.

But it was the third machine in the 100 series that merited an honored place as the first on-air demo in Computer Chronicles history. That was the HP-150. Not long after Cyril Yansouni’s Chronicles appearance, Hewlett-Packard’s Bob Puette made a public presentation on the 150 to the Boston Computer Society, then one of the largest computer user groups in the country. Puette explained that the original HP-125 had not been a success, due largely to the fact H-P announced it the day before IBM launched its own Personal Computer in August 1981. Three months later, in November 1981, H-P started to formulate its strategy for what became the 150.

Hewlett-Packard decided to abandon the 125’s Z80-and-CPM-based design and follow IBM’s lead in using the Intel 8088 micro-processor for the CPU and MS-DOS for the operating system. But to be clear, the 150 was not an IBM PC clone or compatible. H-P did not copy or reverse engineer the IBM BIOS like Compaq or the other early clone-makers. Rather, the 150 relied on “vanilla” system calls in DOS to the Intel CPU. So any software that specifically required those additional calls from the IBM BIOS would not work with the 150.

According to Puette, the move to add the touch-screen began in January 1982, when H-P management decided to combine the personal computer and terminal divisions into a single unit under Cyril Yansouni. At this point, the HP-150’s development team learned about touchscreen research underway at the terminal division’s laboratory. Impressed by the technology, the 150 team decided to incorporate the touchscreen into their machine as an option.

Now, calling the HP-150’s display a “touchscreen” may be a bit confusing to modern consumers who are used to devices like an iPad or a smartphone. Technically, you didn’t actually have to touch the screen on the 150. As Cyril Yansouni explained during his Chronicles demo, the 150’s display relied on a grid of infrared sensors embedded in the bezel of the monitor. When the user’s finger simply hovered over part of that grid, it “broke” the beams at a specific intersection of the X and Y-axes. When the user then removed their finger—allowing the beams to resume—that signaled a “valid hit” to the CPU.

Jim Sutton and John Lee, who led the HP-150’s design team, told Byte magazine in 1983 that they settled on this “optical approach” to the touchscreen because it was cheaper and more reliable than the alternative, which involved placing a special film on the cathode-ray tube monitor to track the movement of the user’s finger. The film approach also reduced the contrast and visibility of the display, which, keep in mind, was a two-color black and phosphor green monitor.

The trade-off, however, was that the film allowed for more precise touch controls. Phil Lemmons and Barbara Robertson, who reviewed the HP-150 for Byte, said that in their testing they had no difficulty “pointing to the defined touch areas at the bottom of the screen, or at the name of a file or program that you want to run,” but it was difficult—if not impossible—to select a specific pixel or text character with any degree of reliability. You still needed the cursor keys to perform “fine” movements.

Despite these limitations, Bob Pouette said that when they performed the first focus group testing of the HP-150 in early 1983, users loved the touchscreen. They loved it so much, Yansouni decided to make it a standard feature rather than an optional extra. This meant making sure there was software ready to use with the touchscreen.

Hewlett-Packard provided some in-house applications bundled with the HP-150. This included the Personal Applications Manager and Personal Card File that Cyril Yansouni demonstrated. H-P also developed MemoMaker, a simple text editor with basic word processing functionality; Financial Calculator, a program that mimicked the company’s popular HP-12C hand-held calculator; and perhaps most notably, VisiCalc, then the industry standard for computer spreadsheet software. VisiCalc initially debuted on the Apple II in 1979, jump-starting sales of that machine in the small business market. Over the next four years, VisiCorp ported its spreadsheet to essentially ever other major computer platform on the market. But VisiCalc, like most early business software, required the user to navigate a complex set of keyboard commands to perform most tasks. So adapting the program for H-P’s fancy new touch-screen required more than a simple port of the existing MS-DOS version. In fact, it took the efforts of a team made up of engineers from HP’s own office computer and office systems teams to develop what was essentially an “extended” version of VisiCalc that maintained backwards compatibility.

Other third-party software developers took on the challenge of developing for the HP-150 in-house. MicroPro International built a special touch-screen version of its popular WordStar word processor. MicroPro employees told Byte that the process turned out to be quite difficult, not because of any technical issues with H-P’s touch-screen interface, but because WordStar itself was written in 14,000 lines of assembly-language code that essentially needed to be reworked line-by-line.

These efforts seemingly paid off, at least for the Byte reviewers, who said the touch-screen improved both VisiCalc and WordStar by making them “much more agreeable” for new and experienced users alike.

Hewlett-Packard formally announced the HP-150 Touchscreen in September 1983, about a month before Cyril Yansouni’s Chronicles appearance. An H-P spokesman told the press that with its new machine leading the way, the company would be “among the top three personal computer manufacturers within two to three years.” Industry analyst Alex Stein, however, told the San Francisco Examiner that he didn’t see the HP-150 as a “final answer” for H-P but it was a “good first step.” Stein said that while H-P still posed no serious threat to industry-leader IBM in the micro-computer, the HP-150 “could take business away from Apple or Tandy.”

Indeed, Apple may have been H-P’s immediate target with the HP-150. During his Boston Computer Society presentation, Bob Puette showed benchmarks that favorably compared the HP-150 to not just the IBM PC but also the Apple II and the Apple III. And during the course of the HP-150’s development, Apple released the Lisa, a $10,000 desktop PC that featured a full-fledged graphical operating system. The Lisa wasn’t compatible with MS-DOS at all and there was virtually no third-party software available. That, combined with the high price point, made it Apple’s second failure to build a business-specific computer after the Apple III.

Of course, even as late as October 1983 it wasn’t completely obvious to the tech press that the Lisa was a dud. In fact, the Lisa was a featured product on the second episode of Computer Chronicles taped that month. And longtime Chronicles contributor Wendy Woods even favorably described the HP-150 at launch as a “Lisa-like Micro.”

Yet even by the summer of 1983, the first rumors had surfaced of Apple’s forthcoming replacement for the Lisa—the Macintosh—which formally debuted in January 1984. In some respects, the Macintosh launch probably blind-sided the Hewlett-Packard folks as IBM had done with the PC two years earlier. The Macintosh, like the HP-150, was built to attract new users who were uncomfortable with the traditional PC command-line interface. But the Macintosh did it with a fully graphical interface controlled by a mouse. Keep in mind, the mouse was not a standard feature of personal computers in 1984. Apple didn’t invent the technology—SRI’s Douglas Engelbart and Bill English developed the first working mouse prototype in 1967—but 1983 was the year when commercial micro-computer manufacturers started incorporating the device into their products. H-P even released a mouse for the HP-150 in 1984 as a $150 accessory.

In retrospect, the HP-150 and the Macintosh offered competing visions for how to make computers more accessible. And the mouse ended up beating the touch-screen, at least in this time period. But the 150 and the Macintosh also shared another feature that marked a significant departure from the IBM PC standard: Both machines had 3.5-inch floppy disk drives as opposed to the five-and-a-quarter-inch drives used by the PC. Again, neither Apple nor HP were first to market with a computer that had a 3.5-inch drive. (The YouTube channel Tech Tangents released a video in 2023 explaining how that honor likely goes to an obscure CP/M-based machine called the Jonos Escort.)

But Hewlett-Packard was the first major U.S. computer manufacturer to embrace the 3.5-inch micro-floppy standard created by the Japanese technology company Sony. In November 1982, H-P announced that the HP-120—the smaller successor to the HP-125—would come with dual 3.5-inch drives a standard option. Similarly, the HP-150 could be configured with dual micro-floppies or a single 3.5-inch drive paired with a hard disk. Unlike the Macintosh, which had a single 3.5-inch floppy disk built directly into the computer and no hard-drive option, the HP-150’s disk drives were housed in a separate unit that fit underneath the main computer and built-in display.

In most respects, the HP-150 was a superior computer to the Macintosh. It wasn’t just more configurable in terms of the disk drives. The entire machine followed Hewlett-Packard’s open approach to architecture and servicing, unlike the closed Macintosh. The HP-150 even had a slightly higher graphics resolution.

The machines were also fairly comparable on price. Apple initially sold the Macintosh for around $2,500, while Hewlett-Packard priced the HP-150 at just under $2,800. But in another move that suggested H-P saw Apple as its immediate competitor in the micro-computer market, the company announced in April 1984 that it would sell the HP-150 at 45 percent below list price—about $2,200—to students at Stanford University. This was in direct response to Apple offering the Macintosh to students at Stanford and other select college campuses for just $1,000.

Ultimately, the Macintosh and the HP-150 served different roles for their respective companies. Apple needed the Macintosh to be a success following the disasters that were the Apple III and the Lisa. Hewlett-Packard, in contrast, wasn’t betting the farm on the HP-150. The company still had a strong mini-computer business, and to a certain extent the HP-150 was simply an extension of that. That’s because while the HP-150 ran MS-DOS locally, it also served as a terminal emulator for the HP 3000 with full graphics capability.

The HP-150 was really more of an evolutionary step for Hewlett-Packard than the revolutionary step promised by the Macintosh. This evolution continued with the launch of the HP-110—more commonly known as the HP Portable—in May 1984, roughly six months after the debut of the HP-150. The HP-110 was a fully portable (mostly) IBM PC compatible with an LCD screen and a battery that promised up to 16 hours of use, all for just $3,000, which was quite a bargain compared to IBM’s own much chonkier portable, the 5155, which released in February 1984 at a price of over $4,200.

Hewlett-Packard did not immediately abandon the HP-150, however. In April 1985, the company announced a successor, the HP-150 Touchscreen II. Despite keeping the name, the second model actually dropped the touch-screen as a standard feature. It was now an optional extra, suggesting H-P realized that there wasn’t enough customer demand or third-party software support for an interface used by no other manufacturer.

The Touchscreen II remained in Hewlett-Packard’s product catalog until around 1989. But by the end of 1985, the company decided to sunset the 100 series and move to its next generation of micro-computers with a PC-AT clone, the $3,200 HP Vectra. The Vectra line went on to be Hewlett-Packard’s mainline series of business PCs until the early 2000s.

Cyril Yansouni’s Read-Rite Adventures

Cyril Yansouni was born in Egypt on June 11, 1942. He emigrated to Belgium at the age of 17 to attend the University of Louvain. While at Louvain, Yansouni met John Linvill, the dean of Stanford University’s electrical engineering school. It turned out the two men were conducting similar research, and Linvill later invited Yansouni to come to Palo Alto on a graduate fellowship.

Yansouni recalled in a 1984 interview with Stewart Wolpin of Professional Computing magazine that he spent 1966 and 1967 earning his master’s degree at Stanford but he “had no specific career goals” other than wanting to someday manage a project. After earning his master’s degree, Yansouni joined Hewlett-Packard in late 1967 as a research and development engineer in the company’s microwave division. He initially worked under Paul Ely, Jr., who later became general manager of H-P’s computer group.

Yansouni also moved to the computer side of the company during the 1970s. He convinced his bosses to let him join a startup team in France that was preparing to market H-P’s 1000 Series mini-computers in Europe. Within a year he was the division’s general manager. By 1981, Yansouni was in charge of three different manufacturing plants under the company’s data terminal division. When Hewlett-Packard decided to consolidate its data terminal and personal computer divisions, Yansouni assumed responsibility for the entire group.

But Yansouni was reportedly frustrated by the internal bureaucracy and overall conservative approach by upper management at Hewlett-Packard. In 1986, he left the company after nearly 20 years to join San Jose-based Convergent Technologies as its new president. Convergent was a struggling computer manufacturer best known for developing the WorkSlate—an early tablet computer released in late 1983—and AT&T’s UNIX PC. In January 1985, the company’s founding CEO, Allen Michels, decided to step aside in favor of a new president, who happened to be H-P’s Paul Ely. Roughly 21 months later, Ely brought in Yansouni to take over as president, with Ely remaining as chairman and CEO. (Incidentally, H-P named Bob Pouette to take over Yansouni’s role as vice president and general manager of the personal computer division, a job he held until January 1990, when he left H-P himself to join Apple as president of its domestic division.)

Yansouni’s arrival at Convergent came as the company reported a $25.7 million loss for the third quarter of 1986. The company’s sales had dropped 45 percent from the comparable quarter of 1985. And just a couple of months earlier, Convergent laid off about 26 percent of its staff.

So it was a fairly dire situation. And, as is often the case when you have a flailing company, the best option is to quickly find a buyer. And that’s exactly what Ely and Yansouni did. In August 1988, Unisys Corporation purchased Convergent Technologies for $350 million. The two companies were longtime partners, as Unisys was a reseller and licensee of Convergent PCs. At the time, Unisys had a particular interest in Convergent’s UNIX systems business, which was then a growing market.

After the acquisition, Ely became an executive vice president and board member of Unisys as well as president of the company’s Network Computing Group. Yansouni was named a Unisys vice president and remained as president of what was now the Convergent Technologies subsidiary.

Initially, there was talk that Ely would eventually succeed Unisys chairman and CEO W. Michael Blumenthal. But in July 1989, Ely abruptly announcement for health reasons. Yansouni then succeeded him as executive vice president and head of the Network Computing Group.

Less than two years later, in February 1991, Yansouni quit Unisys himself and took the top job as chairman and CEO of Read-Rite Corporation. Founded in 1981, Read-Rite was a leading manufacturer of thin-film recording heads for hard disk drives. At the time, Read-Rite had a market share of about 50 percent.

Unfortunately for Read-Rite, about 40 percent of their sales were to a single customer, Western Digital Corporation. And in the early 1990s, Western Digital pushed Read-Rite to make a significant change to the design of its recording heads. Yansouni and his team refused, instead pushing to develop next-generation technology to replace the existing heads altogether. Western Digital didn’t like this plan, so they shifted a major portion of its drive-head orders to Read-Rite’s two main competitors.

Yansouni then backtracked and decided to adapt the change that Western Digital had demanded. But the damage was done. Read-Rite’s earnings and stock price plummeted and one of its competitors, Applied Magentics, launched a $1.7 billion hostile takeover bid in March 1997.

Yansouni successfully thwarted that takeover attempt. But Read-Rite continued to limp along until June 2002, when it filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. In July 2003, a federal bankruptcy trustee auctioned off Read-Rite’s assets. Ironically, Western Digital submitted the highest bid. The trustee rejected the bid, however, fearing antitrust concerns, and recommended awarding the Read-Rite assets to a group composed of three other companies. The bankruptcy judge overseeing the case subsequently decided to hold a second auction. This time, Western Digital submitted an even larger bid and won.

Cyril Yansouni remained with Read-Rite until the final bankruptcy sale in 2003. Since then he’s served as a director for a number of companies. He’s also currently the president of the Carmel Bach Festival, an annual series of four-day concerts held in Monterey County, California.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was recorded on October 31, 1983.

- If you would like to see a full demonstration and tear-down of the HP-150, Adrian Black of the YouTube channel Adrian’s Digital Basement posted just such a video in September 2020.

- During their podcast interview, Leo Laporte mentioned he actually worked with Stewart Cheifet at Hewlett-Packard “a long time ago.”

- SRI’s Herbert Lechner will be a recurring guest (and occasional host) on The Computer Chronicles during this first season.

- KCSM-TV, where Cheifet produced Chronicles as general manager, was originally established by the College of San Mateo in the 1960s as a student broadcast training facility. In 2017, Sonoma County public television (KRCB) acquired KCSM and changed its call letters to KPJK. The KCSM call sign is still used for an FM radio station that specializes in jazz programming.

- During this first season, the presenting sponsor for The Computer Chronicles was Micro Focus, an enterprise software company that remained in business until August 2022, when it was acquired by OpenText.

- The Computer Museum of Boston, the subject of the first feature segment, closed in 2000, at which time most of its collection was re-homed at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.