Computer Chronicles Revisited 44 — Thelma Estrin, Judith Estrin, Elizabeth Stott, Kay Gilliland, Jan Lewis, and Adele Goldberg

There’s a telling comment from the previous Computer Chronicles episode that helps set the stage for this next program. When discussing the state of the computer software industry in late 1985, Electronic Arts founder and CEO Trip Hawkins said the market was driven by men who were primarily interested in entertainment. He explicitly said “men.”

The notion that computer games–and by extension, computers in general–were just for “men” reflects the larger problem of sexism that continues to plague the tech industry even today. Keep in mind, the problem was even worse in 1985 when access to computers was still a luxury for most people. This only exacerbated the difficulties for women looking to enter the male-dominated culture of computer engineering. In June 1985, Stanford University released a study that found only about one-third of computer programmers and analysts were women–and the women who held those jobs earned “far less” than their male counterparts.

This next Chronicles episode largely focused on the positive, however, showcasing a number of women who were successful in various facets of the computer industry and looking at efforts to expand computer access for younger girls through education and gaming.

Computers Failed to Prove an “Equalizer” Among the Sexes

Stewart Cheifet opened the program standing next to a group of children using computers at San Francisco’s Exploratorium. He noted there were just as many girls as boys visiting the exhibit, suggesting that the stereotype that computers were mainly for boys and men was incorrect.

Back in the studio, Cheifet and Gary Kildall looked at Cave Girl Clair, an adventure game developed by Rhiannon Software for the Apple II, which featured a playable female main character. Cheifet noted that most adventure games–indeed, most computer games–were aimed at men. Many people had thought computers and high-tech would be an equalizer among the sexes. Yet Cheifet said most computer engineers, programmers, and scientists were men. What explained this continuing gender gap? Kildall said the computer industry was based in general engineering, which was a male-dominated field. That said, the industry also thrived on talent and innovation rather than artificial biases and barriers. Kildall said he didn’t quite know the reason for the gender gap. But he added that in his personal experience, his son was a “computer nut” while his daughter loved horses, and he couldn’t say what he did to influence those preferences.

Computing’s Gender Gap Grew as Students Aged

Wendy Woods presented her first remote piece for this episode, recorded at an unidentified elementary school. She said that computers in the classroom were no longer scarce. Computers were now commonly introduced to both boys and girls as early as the first grade. But while the sexes were about equally divided when it came to computer usage in elementary school, the ratio changed in later years.

Woods said that a recent study indicated that first-grade girls were just as likely to use computers as boys. But by the sixth grade, the boys outnumbered the girls 2-to-1. And by the time students left junior high school, boys made up 80 percent of the group learning to program computers.

Educators cited different reasons for this discrepancy, according to Woods, from “intimidation” and “parental pressure” to the dominance of male-oriented games in educational software. But while it may be a simple job to count heads in a classroom, Woods said, it was harder to keep track of the computer’s influence outside of school.

Woods then shifted to profiling Cory Grimm, a 16-year-old woman who worked as a graphic artist for her mother’s software company. (There is no on-screen chyron, so I’m guessing at the spelling of this woman’s name.) Woods said that Grimm had been working with computers since the age of 10, using a joystick, mouse, and electronic palette to create art. Unlike many artists who were reluctant to trade the tactile sensations of a paintbrush for a light pen, Woods said, Grimm began her graphic arts career with the computer as her primary tool. She also had three computers at home, programmed in BASIC, and did her homework on a Macintosh.

With the help of teacher workshops, Woods said, female enrollment in computer classes had expanded recently. And some software vendors, hoping to find a new market, continued to develop programs specifically designed for women. But, Woods added, Grimm managed to incorporate computers into her own life without worrying about this.

UCLA Professor Recounted Journey as an Early Woman in Computer Science

This was a guest-heavy episode. The first of three round tables featured a mother-and-daughter pair, Dr. Thelma Estrin and Judith Estrin, respectively. (For the sake of clarity, I will identify each woman by their first name.) Kildall opened by asking Thelma, a professor of computer science at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), how she managed to get into a traditionally male-dominated field like engineering when she did. Thelma said that during World War II, she had an opportunity to work in an engineering lab because the men had gone off to fight. After the war, Thelma said she decided to go back to school and major in engineering. She was able to ultimately earn a Ph.D in electrical engineering.

Kildall asked if that was rare for a woman back then. Thelma replied it was “very” rare. She was married to her husband Dr. Gerald Estrin–who also held a Ph.D in electrical engineering–and most people thought she was in school either to do his homework or to keep her “out of mischief.” But they both went on to have successful careers. Gerald Estrin had an opportunity to work at the Institute for Advanced Study in New Jersey with Dr. John von Neumann. Thelma also worked at the Institute for a summer before going into a different field, biomedical engineering, and later shifting back to computer engineering.

Kildall asked Thelma if she’d seen the attitudes shift over the years. Thelma said yes, there’d been a tremendous shift. Early in her career, people would tell her, “You don’t look like an electrical engineer.” She didn’t think people would tell a woman today, “You don’t look like a computer scientist.”

Kildall then turned to Judith, who was then an executive vice president with Bridge Communications, a local area networking company, and asked about the impact of her mother as a role model for her own career. Judith said her mother had helped encourage other women to enter the computer and engineering fields. Judith said she never questioned whether she should move into a “man’s profession” after watching her mother do it. She did note, however, that she still got some pushback from men who said she “did not look like an executive VP of research and development.”

Cheifet asked Judith for how things were going for women of her generation versus what her mother had to deal with when she got started. Judith said you had to separate the individual contributor and the first-level managers from upper-level management. At the engineer level things had changed dramatically for women. Judith said she entered the industry with young men who were very accepting of her as a colleague. Overall, she had experienced very few obstacles in her career. But at the higher levels of management, women tended to be at the top of companies they had founded. (Judith is actually referencing a point made later in the program by Jan Lewis, so presumably this segment was taped after that one.) So there were still obstacles for women in that respect, and that mainly came down to the attitudes of people in upper management.

Kildall followed up, asking if that was an attitude held by people in business generally speaking, or was this specific to the computer industry. Judith said it was business in general. She thought the computer industry was more advanced in its attitudes, because it was a young industry driven by younger people who grew up in a world where women were more accepted. But sexist attitudes had not disappeared.

Cheifet asked Thelma, who taught computer science at UCLA, about the male-female ratio with respect to her own classes. Thelma said that she taught primarily at the graduate level, and UCLA also had a large group of Asian-American students. Within that community, she said you saw almost as many women as men in engineering and computer science, both at the graduate and undergraduate level. Cheifet asked, “More so than among the Americans?” Thelma said yes. Among “Americans,” she said only about 10 to 15 percent of graduate students were women, with about 20 percent at the undergraduate level.

Were “Games for Girls” the Answer?

The next round table featured Elizabeth Stott and Kay Gilliand. Kildall asked Stott, the co-founder of Rhiannon Software, if she felt that the software currently available for the home computer market made girls feel that it was “not okay” to work with computers. Stott, who was also a psychologist, said that was true of most of the available software. She said that the artwork, content, gameplay, and advertising all said, “Hey, this a boy thing!” The whole industry send the message this was a “male machine.” She analogized the industry’s current attitude to how back in the 1920s, a woman wouldn’t be seen driving a car.

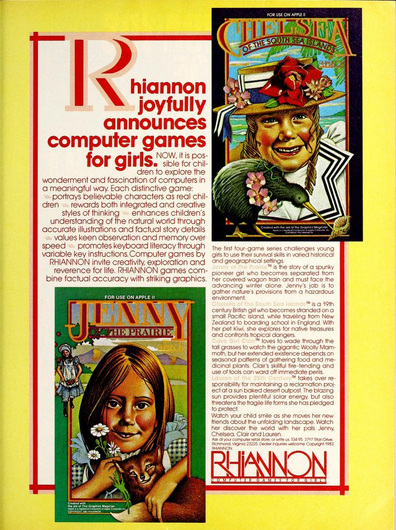

Overall, Stott said there was an enormous psychological barrier that girls had to overcome with respect to computers. To address this, Stott said Rhiannon’s games featured “very appealing, realistic, spunky, fun, energetic” girl characters having neat adventures. (To give you an idea of what these games looked like, I’ve included a screenshot from Rhiannon’s first game, Jenny of the Prairie, below.)

Kildall asked Stott to further elaborate on the differences between Rhiannon’s software and more “boy-oriented” titles. Stott said the characters was one difference. She said the style of the graphics was another difference–they were drawn at a rate that the eye could follow, which was very appealing. She said people tended to “lean into” the computer when they first saw the graphics rather than “leaning away” as they did with other software.

Stott then demonstrated one of Rhiannon’s programs. She never actually identified the name of this game, but it was Sarah and Her Friends. Stott explained they’d had such a positive response with their previous series of adventure games for 7-to-12-year-old girls (including Cave Girl Clair), that they designed Sarah for 4-to-8-year-olds. Unlike the adventure games, Sarah did not require any reading.

As is frequently the case with software demonstrated on Chronicles, it’s hard to actually learn much about the program from the guest’s piecemeal descriptions. So I actually ran Sarah, which is available via emulation from the Internet Archive. From Stott’s description, the entire program only uses three keys: return, escape, and the space-bar. The program opens with you selecting a group of “friends” from a bunch of avatars. Then you’re taken to the main menu, which displays five options. (This is all done in pictures because as Stott noted there is no text.)

Each option leads to a mini-game involving some sort of pattern matching. For example, if you select the umbrella image you’re taken to a screen where the player is asked to match an appropriate item of clothing to the weather seen outside of a “window.” If you make the correct selection a short celebratory tune plays.

Kildall asked if the whole idea here was that by playing this game, the child would learn it was okay to work with computers. Stott said the child identified with what’s going on and took it into their real life. She said Rhiannon’s goal was to make computer games that matched the children. So the goal was to encourage experimentation and learning what the computer could do.

Cheifet asked Stott if she ever saw boys playing with Rhiannon’s games. Stott said the extraordinary thing was that even when a game had a girl on the cover and was explicitly marketed towards girls, boys would still show interest simply because it was a new computer game. Stott said this showed the extent to which the computer was a “male-identified machine.” Meanwhile, girls would say, “Oh, I didn’t know they had anything for girls.” And then after they played the game, those girls would go on to try other kinds of software. Stott said that was the whole point of Rhiannon Software–to crash that barrier.

Kildall then turned to Gilliland, the director of the EQUALS program at the University of California at Berkeley’s Lawrence Hall of Science, and asked about the importance of introducing computers to young girls. Gilliland said it was very important to use whatever entry point that we had to make sure girls experienced computers. She noted that many of the things that Rhiannon had done were used in the home and helped tremendously. However, something also had to be done in the schools.

Gilliland added that many parents weren’t even aware of the gender gap when it came to computers. She recounted a recent anecdote from her work at Lawrence Hall. A group of preschoolers–all boys–were using the Hall’s computers. Gilliland asked one of the mothers if her son was in the group. He was. Gilliland asked if he liked using the computer. The mother said he did. Gilliland then asked if the mother also had a daughter. She did. Was she was also interested in computers? The mother replied, “Oh, we never thought about it for her.” Gilliland noted this was an intelligent woman but our whole society sent the message that computers were for boys. Kildall agreed with Gilliland that it was up to our educational system to make sure that we introduced computers in a way that did not have any gender orientation.

Cheifet said he’d seen some startling numbers from research done at Lawrence Hall. Specifically, only 7 percent of home computer users were women, 5 percent of the subscribers to BYTE were women, and just 2 percent of PC buyers were women. Why did Gilliland think those numbers were so low? Gilliland said our culture sent a message to girls when they were very young that computers were not for them. She noted, for example, that every picture used in the manual for the Apple Macintosh showed a man using the machine. There were no pictures of women. (She’s right, I checked.) There were ultimately many reasons for low computer usage among women, she said, but it started with greater awareness among parents and teachers. Gilliland noted that her own program, EQUALS, was started in 1977 as a teacher education program for mathematics. It had now expanded into computer technology.

Cheifet asked about the type of software that EQUALS used. Gilliland showed a copy of Gertrude’s Secrets, an educational puzzle game published by The Learning Company widely used by teachers looking for “bias-free” software that was equally appealing to boys and girls. Kildall asked how Gertrude’s Secrets accomplished that. Gilliland pointed to the lack of violence, noting that many girls were not attracted to programs like wargames. And obviously, many teachers did want to promote violent games in their classroom. So the goal was to present things that both girls and boys enjoyed. She added that the educational component was just as important. Games that taught spatial relationships, for example, were useful as that was an area where girls had traditionally experienced difficulties.

San Francisco Project Offered Women Vocational Computer Training

Shifting the focus from children to adults, Wendy Woods presented her second remote segment, this time from the Women’s Computer Literacy Project (WCLP) in San Francisco. Over some B-roll of women seated at a bank of computers, Woods said they all had one thing in common–they knew nothing about how the machines worked. They were students at the WCLP, which Woods described as an intensive two-day course for women-only where instructor Deborah Brecher taught computer basics in a “unique and controversial way.”

Brecher also wrote a companion text, The Women’s Computer Literacy Handbook, in which she claimed that women learned differently from men. While men could memorize a set of instructions and then follow them, women required an understanding of the concepts and the machines before they could fool around with them. Brecher told Woods that she’d been looking at research to see if that was true. What she found was that in game theory, boys learned rules-based games very young while girls played more process-based games (like dolls) that weren’t based on rules. Brecher said that early childhood patterning led into gender differences about styles of learning.

So what women were taught at the WCLP, according to Woords, was analogies. For instance, Brecher compared a memory buffer to a bathtub and random access memory to mailboxes. Brecher said that since her classes were all-female there was a certain common background that she could assume, such as that everyone knew how to cook. And if they knew what ingredients in a recipe were, they could learn that “data” provided the ingredients for a computer’s “recipe,” i.e., programs.

Woods said that approximately 3,500 women–ranging in age from their teens to their 70s–had taken Brecher’s course, which was the only one of its kind in the United States. Brecher said she’d received letters from hundreds of students thanking her for teaching them “all they needed to know” about computers.

Were Women Headed in the Right Direction?

Back in the studio, Adele Goldberg and Jan Lewis joined Cheifet and Kildall for the third and final round table. Kildall asked Goldberg, the manager of the research laboratory at Xerox PARC, if she saw the emergence of a software market specifically targeting women. Goldberg said she didn’t distinguish between men and women. All she saw was people and her goal was to excite all children and adults about software.

Cheifet asked Lewis, a computer industry veteran who was then serving as president of the Palo Alto Research Group (not to be confused with PARC), about the hurdles or problems she faced as a woman in computing. Lewis said while there probably were hurdles and problems, she didn’t realize it until about five years ago. When she got out of college she wanted to be a programmer because that was considered a good field for women. In 1974, she moved into sales with a company called Infomatics. There, Lewis was the first female hired to work on a 100-person sales force. These days (1985), Lewis said the typical high-tech sales force was about equally divided between men and women.

But even when she worked at Infomatics, Lewis said she still wasn’t thinking about discrimination. It was only when you started getting towards the top that you realized there were more opportunities for a woman if you went off and started your own company. Kildall said that seemed to be a recurring theme–that it was more difficult for women to penetrate the upper levels of management at an established company. Lewis said there were exceptions, but for the most part women reached the upper levels at their own company. That said, Lewis said she didn’t have any problems as a woman dealing with clients, employees, or suppliers in running her business. She simply ignored the obstacles and strived to be the best.

Cheifet asked Goldberg if girls who didn’t get early experience with computers would be at some disadvantage when they became adults. Goldberg said it was true of both girls and boys. It was becoming more imperative for everyone to have an understanding of what computers were about and how you could use them. Goldberg said that in addition to role models, younger computer users also needed to see jobs related to their interests. Goldberg said she wouldn’t hire anyone who didn’t have some computing experience and done real work in the field even if they just graduated from school.

Cheifet mentioned Kildall’s daughter, who preferred horses to computers. Should a parent be concerned by this lack of interest in computers? Goldberg quipped there were days when she didn’t like computers and would rather have horses. But no, she didn’t think it should be a concern. Different people were interested in different things. Goldberg noted that she didn’t have computers in the home with her two daughters–they were learning piano and art. As they grew up their interests would change, and she did expect schools to provide some computer experience.

Kildall asked if we were heading in the right direction in getting more women involved with computers. Lewis said absolutely, particularly at the early levels. She said children had a natural inquisitiveness and as long as nothing stood in their way–i.e., as long as there was a computer for them to play with and nobody thought it was something verboten–things would trend in the right direction. Lewis also disagreed with the Lawrence Hall survey’s claim that women made up only 2 percent of PC buyers. In her own research, Lewis said that percentage was increasing dramatically among business buyers.

A “Terrible Waste of Human Resources”

Paul Schindler offered his closing commentary “as the father of two girls.” He noted that he recently wrote a cover story for Information Week about women in computing. And he was “mad as hell” to see how much women were still underused in the computer business. He said women should be angry because the “accident of your birth” put you at a permanent disadvantage in the computer business. It might be less of a disadvantage than in other fields but it was still a disadvantage. Schindler said men should be equally angry at this “terrible waste of human resources.”

Schindler said that he certainly hoped that nobody was arguing that women weren’t as smart as men. So there was no reason that women shouldn’t be at least half of the computer industry workforce. To be clear, he wasn’t saying “hire women because they’re women,” but rather, “Hire the best person for the job regardless of sex.”

Apple Clone-maker Re-Entered the Market

Susan Chase–formerly known as Susan Bimba–returned for the first time this season to present “Random Access” in place of Stewart Cheifet. This segment was produced sometime in September 1985.

- Franklin Computer Corporation unveiled its first Apple-compatible clone following bankruptcy and a lengthy legal battle with Apple. The new Franklin Ace 2000 would come in three models priced under $1,000–about $600 less than the Apple IIc and IIe models.

- As for Apple, Chase said it continued to improve its own products. Apple announced a IIe upgrade to expand the machine’s memory to almost twice that of the IBM PC. Apple also planned to release a higher-capacity floppy disk drive, a color monitor, and software to make the Apple II run more like the Macintosh.

- Jack Tramiel’s Atari Corporation was reportedly negotiating a deal to sell its 520ST computers through AT&T. Chase said this would give Atari a “major customer” for its new computer while providing AT&T with a low-cost entry into the PC market. Both companies, however, formally denied there were any negotiations.

- A new program called Javelin planned to offer stiff competition for Lotus 1-2-3 by giving users the ability to look at their data in almost a dozen different forms. The program would sell for $700 and require an IBM PC with at least 512 KB of memory.

- Finally, Paul Schindler provided his weekly software review, this time for Da Vinci (Aplied Microsystems, $60), an outline program. Schindler said each outline could contain up to 5 levels with 99 topics each, although there was an overall limit of 255 headings. The finished outline could then be exported to a word processing program.

Looking Back at Remarkable Women in Computing

This was perhaps the longest episode of Chronicles that I’ve reviewed to date. The recording took up 29 minutes and both the opening and closing credits were removed. This was not surprising given there were three round tables and two remote features packed into the show. Before moving on to the main topics of my analysis, the history of Rhiannon Software, I would like to briefly acknowledge the backgrounds and legacy of four of the in-studio guests.

Dr. Thelma Estrin (1924 - 2014)

Dr. Thelma Estrin was born in New York City. Estrin–whose maiden name was Austern–said her mother had pushed her to become a lawyer. Austern entered the City College School of Business Administration in New York City, where she met her future husband, George Estrin.

After the United States entered World War II, Thelma Estrin took a three-month course at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey to become an engineering assistant. This led to Estrin’s first job at Radio Receptor Company, an electronics manufacturer. After the war, Estrin and her husband both attended the University of Wisconsin to study engineering. Thelma Estrin would earn her bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees at Wisconsin.

The Estrins then returned to the east coast, where Thelma took a position at Columbia University’s medical school. This was where Estrin developed her specialty in biomedical engineering. In the mid-1950s, Estrin joined her husband on a project to build Israel’s first computer, the WEIZAC. After completing that project, Gerald Estrin took a position at UCLA in 1956. Thelma Estrin joined him there in 1960 after a stint teaching at a community college.

Thelma Estrin worked for UCLA’s newly established Brain Research Institute, one of the first biomedical research centers to use computers. Estrin oversaw the laboratory and taught classes on biomedical computing. She was named director of the laboratory in 1970 and held that post for a decade.

In 1980, Estrin moved to UCLA’s computer science department as a professor. After spending a couple of years teaching undergraduates, Estrin served as director of the engineering and computer science division for the National Science Foundation from 1982 to 1984. She returned to UCLA afterwards, and later served as an assistant dean in the engineering school. Estrin retired from UCLA in 1991. She passed away in 2014.

Judith Estrin was one of Thelma Estrin’s three children. At the time of this Chronicles episode, she was a co-founder and executive vice president at Bridge Communications. Bridge was one of the first companies to develop commercial networking routers. 3Com acquired Bridge in 1987. Judith went on to start several more tech companies and served as chief technology officer for Cisco Systems in the late 1990s. She currently runs JLabs, LLC, a private consulting firm.

Kay Gilliland (1928 - 2013)

The other guest from this episode who has since passed away was Kay Gilliland. According to a short biography published by the California Mathematics Council, Gilliland was born in England and raised in Los Angeles. She graduated from Mills College in Oakland and worked as a math teacher in California, Hawaii, and Washington, DC.

In the late 1970s, the University of California, Berkeley, created the EQUALS project, which was designed to improve the math curriculum for girls in elementary and secondary schools. Gilliland was one of the first staff members at EQUALS. She went on to spend 20 years with the project, ultimately filling a number of director-level roles.

Towards the end of her life, Gilliland returned to Mills College, where she served as a student teacher supervisor in mathematics and science. Gilliland died in October 2013. The National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics (NCSM) has honored her since then by presenting the annual Kay Gilliland Equity Lecture Award in her memory.

Goldberg Played a Crucial Role in Creating the Modern GUI

Dr. Adele Goldberg was born in Cleveland in 1945. She attended the University of Michigan where she earned her bachelor’s degree in mathematics. In a 2010 interview conducted by John Mashey of the Computer History Museum, Goldberg said her initial goal was to become a math teacher. But when she realized that she’d have to take a public speaking class to get her teaching certificate, she decided to pursue a career in computers instead.

Goldberg went on to earn her master’s degree and doctorate at the University of Chicago. She told Mashey that her experience somewhat paralleled that of Thelma Estrin in that she was only able to get a fellowship because too many male students were off fighting the war (in Goldberg’s case, Vietnam).

While enrolled at Chicago, Goldberg actually completed her dissertation research at Stanford. Goldberg said Chicago didn’t have the funding for educational technology, which was her area of interest. So she got permission from Stanford’s Patrick Suppes–a former Chronicles guest himself–to complete her dissertation there as a research associate.

After completing her doctorate and briefly teaching in Brazil, Goldberg joined Xerox PARC in 1973. She was part of the team that developed Smalltalk-80, an object-oriented programming language that helped form the basis for computer graphical user interfaces, including the original Macintosh operating system. Goldberg also worked with her Smalltalk colleague, Alan Kay, in outlining the “Dynabook” concept, which proposed a tablet-like educational computing device specifically for schoolchildren.

At the time of her Chronicles appearance, Goldberg was serving a two-year term as president of the Association for Computing Machinery. Goldberg continued to work at Xerox PARC until 1988, when she left to start her own company, ParcPlace Systems, which continued to develop Smalltalk-based applications. She served as ParcPlace’s CEO initially and later as board chairman. In 1995, ParcPlace merged into a competing firm, Digitalk.

After ParcPlace, Goldberg founded one other company, Neometron, Inc., and continues to serve as a consultant to the present day, most recently as a member of the scientific advisory board for the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies in Germany.

Rhiannon Partnership Struggled to Make Its Mark During Brief “Bookware” Period

Unlike most software companies we’ve seen featured so far on Chronicles, Rhiannon Software was never organized as a corporation. Rhiannon was a general partnership formed by Elizabeth Stott and Lucy Werth Ewell. As Stewart Cheifet mentioned, Stott’s background was in psychology. She was a licensed professional counselor practicing in Virginia. Ewell had a technical background as a computer systems analyst.

Since there’s no publicly available filings for a partnership it’s difficult to pinpoint Rhiannon’s exact date of formation, but it was likely sometime in late 1982 based on reports that it took Stott and Ewell about nine months to develop their first game. That game was Jenny of the Prairie. According to an October 1983 filing with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Stott and Ewell first used the Jenny name “in commerce” on August 1, 1983. The trademark filing also lists the name of Stott and Ewell’s partnership as “Computer Games for Girls” doing business under the trade name of Rhiannon.

Jenny was almost certainly published before August 1983. In a separate filing with the U.S. Copyright Office, the date of publication was listed as May 15, 1983. More importantly, the first known advertisement for Jenny appeared in the classified section of Ms. magazine’s March 1983 issue. That ad solicited mail orders (using Stott’s home address) and listed the publisher’s name as “Computers for Girls” rather than the later “Computer Games for Girls” or Rhiannon Software.

A May 1983 publication date seems most likely, however, based on a full-page print ad that appeared in Softalk magazine’s issue from that same month. This ad used the name Rhiannon for the first time and advertised both Jenny and a second game, Chelsea of the South Sea Islands.

The first press coverage of Rhiannon appears to have been a July 12, 1983, column in the Boston Globe by Ronald Rosenberg, which quoted Stott promising two additional games–Cave Girl Clair and Lauren of the 25th Century–for release later in 1985. Stott told Rosenberg that she planned to market the games herself starting in August 1985 and that she had turned down an offer of venture capital funding because, “I just did not want to see a bastardized product.”

Rhiannon’s copyright filings list an August 15, 1983, publication date for Clair. The publication date for Lauren is unknown as I could not find any copyright filing. Indeed, Lauren is something of a mystery as it is the only Rhiannon program that has not been archived by any known online repository, such as the Internet Archive. But the game was advertised together with the other three programs in 1984 and 1985, so it presumably did come out at some point.

Although Stott seemed to resist using an outside distributor initially, she and Ewell eventually signed a publishing deal with Addison-Wesley sometime in late 1983 or early 1984. Addison-Wesley was (and still is) best known as a publisher of textbooks. During the period from roughly 1984 to 1986 there was an attempt by many traditional publishers like Addison-Wesley to enter the software market with so-called bookware, i.e., adventure games with a literary bent. Addison-Wesley had published one of the more successful bookware titles, an adaption of The Hobbit imported from the United Kingdom, and it also marketed the four Rhiannon adventure games for girls during 1984 and part of 1985.

By the time Stott appeared on Chronicles in September 1985, however, Rhiannon was back to self-publishing its software. It was in this post-Addison-Wesley period that Stott and Ewell released their final two products, Sarah and Her Friends and Kristen and Her Family. Unlike the previous four games, which all focused on a lone female protagonist surviving in some sort of outdoor camping environment, Sarah and Kristen emphasized the female character’s interactions with groups. In Kristen, for example, the player chose a home for her “family” and played mini-games that mimicked performing chores.

The last news articles to discuss Rhiannon Software appeared in March 1986. After that it’s unclear exactly when and how Rhiannon ceased operations. I was unable to find any information regarding the post-Rhiannon career of Lucy Ewell. As for Elizabeth Stott, she remained a practicing therapist in Virginia until 2003 and is presumably retired at this point.

Judging by the amount of press clippings Rhiannon accumulated between 1983 and 1986, its emphasis on “software for girls” certainly generated a lot of buzz. We don’t know how that translated into sales as Rhiannon never published any such figures to my knowledge. And not all of the press attention was positive. Interestingly, Stott and Ewell’s work faced significant criticism from contemporary feminist scholars and other women working in technology education.

For example, the spring 1986 issue of Feminist Collections, a quarterly journal published by Thelma Estrin’s alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, featured a write-up by UW Professor Elizabeth Ellsworth that cited one of her colleague’s views regarding “computer games for girls”:

In a recent interview, Dr. Mary Gomez, lecturer in Elementary Education at [UW] questioned the implications of Rhiannon Software for antisexist education. The girl user is put in the traditional female role of helper and nurturer, thus perpetuating stereotypical gender roles. This type of software also threatens to perpetuate sexist notions about what girls like vs. what boys like. Gomez referred to research that shows that both boys and girls enjoy many different kinds of learning–e.g., intrinsic and extrinsic; competitive and cooperative; open ended patterns, movements, and colors as well as lineal sequential goal seeking. “Computer can offer any of these. We need to offer all kids varied entry into technology as individuals,” Gomez said.

Along similar lines, a January 1986 feature story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette offered comments from Nancy Kriesberg, the director at the University of California’s EQUALS program and a colleague of Kay Gilliland, who said that while Stott and Ewell had their hearts in the right place, “I don’t think you have to have programs for girls. If you have good, challenging software, you don’t have to have sex differentiation.” As Gilliand did on Chronicles, Kriesberg pointed to the educational games produced by The Learning Company as a good example of quality software free of gender bias.

Despite the criticism, the Rhiannon games seemed to review well. Scott Mace of InfoWorld offered an overall positive assessment in an April 1984 column. To his credit, Mace didn’t rely solely on his own assessment–he asked the 13-year old sister of a colleague to play the games and offer her thoughts. The colleague reported back as follows:

I thought [my sister] Sally would be somewhat turned off because these are games for girls–Sally enjoys video games that most girls don’t care for.

My preconceptions were wrong. Not only was she intrigued by the games, but also her patience lasted longer than did mine. In Cave Girl Clair, Clair, accompanied by her pet rabbit, must learn to survive on her own. “It’s different from a lot of other games,” Sally said. “You have to play it more than once.”

Sally did feel, though, that this game had too many controls and that it was too complicated for her to master in a half-hour sitting. She liked the second game, called Jenny of the Prairie, a lot more, although she couldn’t understand what some of the graphics represented.

These comments hint at why Rhiannon Software did not enjoy any sustained success in the market. Adventure games were a tough sell to children regardless of sex. The adventure game was rooted in text-based programs developed for university mainframes–the genre is named for Colossal Cave Adventure, originally programmed for the PDP-10–and relied on quirky interfaces and often convoluted puzzle design. Later adventure games, such as Sierra Online’s King’s Quest series, which debuted in 1984, took this latter idea of “moon logic” to even greater extremes while adding graphics and a fantasy world setting. For their part, Rhiannon’s games adopted a similar (although less polished) graphical approach to Sierra’s while making the puzzles and settings much more realistic.

That realism may have also been to Rhiannon’s detriment. In the manual for the Atari release of Cave Girl Clair, for instance, the player is told, “If [Clair] is lucky, she may find a carcass in the grassland. She can carry the hide and bones back to the cave.” That’s pretty raw for a game targeting pre-teenage girls.

It’s especially odd given that the cover designs and packaging for Rhiannon’s games exclusively portrayed young white girls from well-to-do families. Stott herself admitted in later interviews that the cover designs were too “WASPy.” Beyond that, at least one game engaged in racist stereotyping. The marketing copy for Chelsea of the South Seas referred to the main character–a New Zealander heading to England to attend boarding school–needing to avoid “cannibals” while stranded alone on an island.

Setting that aside, I suspect Rhiannon got caught between something of a rock and a hard place. Their initial push as a self-publisher and later through Addison-Wesley was to market their adventure games directly to parents with home computers, primarily the Apple II. But as we learned from the previous two episodes, the home computer market was not growing much during this time period. And the dominant platform for home computer gaming was rapidly becoming the Commodore 64, not the Apple II.

Of course, the Apple II was the dominant computer platform in schools and would remain so well into the early 1990s. But Rhiannon’s approach to adventure games wasn’t conducive towards attracting teachers for the reasons cited above. Meanwhile, there was another Apple II-based adventure game released in 1985 that targeted children and ultimately proved highly appealing to teachers and schools–Brøderbund’s Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?

Carmen wasn’t initially a big commercial hit but gained support through word-of-mouth among teachers who used the game to teach world geography. Unlike Rhinannon’s adventure games, Carmen offered a simple menu-based interface and a much tighter focus on education. It also didn’t hurt that the “Carmen Sandiego” character was generally portrayed as a non-white woman, even if she was the game’s antagonist rather than a playable protagonist. (Carmen led a “gang” of male and female characters that the player had to pursue by interpreting geography-based clues.)

Games like Carmen helped launch the late 1980s “edutainment” wave in computer software, which established publishers like Brøderbund dominated. This left little room for niche publishers like Rhiannon, whose adventure games were likely already considered outdated by 1986. Rhiannon’s final effort to pivot to more open-ended games like Sarah and Her Friends was probably a good idea, but it seemingly came too late.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of September 17, 1985.

- Special thanks to Kate Willaert, a video game historian who graciously provided me with her own research materials on Rhiannon Software and offered some valuable insights on the company’s products.

- I do have more to say about Deborah Brecher and the Women’s Computer Literacy Project, but given this post is nearly 7,500 words, I decided to move that discussion to a future special post.

- The other guest in this episode, Jan Lewis, will become a regular Chronicles contributor, so I’ll delve more into her biography at a later time as well.

- Dr. Adele Goldberg once served on the board of trustees for the Exploratorium in San Francisco, where Stewart Cheifet did his opening standup for this episode.

- Dr. Thelma Estrin had another daughter, Dr. Deborah Estrin, who followed her mother into the field of medical technology. Dr. Deborah Estrin is currently a professor of computer science at Cornell Tech, where she is also an associate dean. Deborah Estrin also previously worked at UCLA, just like both of her parents.

- Elizabeth Stott’s touting the unique “style” of graphics in Rhiannon Software’s games was a bit misleading. In fact, Rhiannon used an off-the-shelf program, The Graphics Magician, by Jon Niedfeldt and Mark Pelczarski, to design all of their adventure games. Magician used vector-based commands to draw images without the need to store them on the disk. A number of adventure games in this time period used similar systems, including Sierra’s King’s Quest series.

- The Learning Company game Gertrude’s Secrets mentioned by Kay Gilliland was co-authored by Warren Robinett, who previously developed another landmark adventure game–Adventure for the Atari 2600.

- The rumored AT&T-Atari distribution deal for the 520ST was just that, a rumor. Atari Corporation President Sam Tramiel, one of Jack Tramiel’s sons, told computer columnist James Calloway in November 1985 that the two companies were talking about a deal–but to license UNIX for Atari’s planned successors to the 520ST. Atari did release a machine in 1990,the TT030, that was capable of running UNIX and was one of the earliest machines adapted to run Linux.

- The makers of the Da Vinci outline software were apparently so confidant in their work that, according to a review in InfoWorld, they offered to send any dissatisfied customers a free copy of a competing program, Max Think.

- Rhiannon Software was named after a figure from Welsh mythology. Also known as the “Goddess of Birds and Horses,” Rhiannon was falsely accused of murdering her son and forced to carry visitors to her husband’s castle on her back like a horse.