Computer Chronicles Revisited 68 — Fontographer, the Radius Full Page Display, DeskTop Art, and Ready, Set, Go!

In September 1986, roughly 1,000 people attended the first Seybold Conference on Desktop Publishing, where the featured speaker was exiled Apple co-founder Steve Jobs. As usual, Jobs was desperate for attention, so he proceeded to insult the participants by telling them, “You’re here at a $600,000 event to talk about a non-existent industry in two years.” According to Wendy Woods’ Newsbytes, Jobs apparently believed that companies would soon offer “computers with built-in software for desktop publishing,” rendering the standalone software market obsolete. (Spoiler: That didn’t happen.)

The hippie grifter no doubt resented the fact that desktop publishing (DTP) had saved his beloved Macintosh from the same ignominious fate as the Apple III and the Lisa. As Woods noted in that same report, by late 1986 Apple “was selling one laser printer for every three Macintoshes.” On the software side, Paul Brainerd of Aldus said his company had already sold 30,000 copies of its PageMaker DTP package, which was super numbers for a Macintosh program of the time.

Brainerd appeared on the next two Computer Chronicles episodes, which were dedicated to the growth of desktop publishing. This first episode from October 1986 focused on the Macintosh side of the market. Stewart Cheifet noted in his cold open that DTP software enabled small groups like a community association to produce its own newsletter. Another example was ComicWorks, a Macintosh DTP package used to make comics, which he showed to Gary Kildall in the studio introduction.

Cheifet reiterated that DTP had made–and perhaps saved–the Macintosh. Kildall added that the IBM PC standard originally included only a character-based display and only later adapted CGA and EGA graphics. And DTP required a hi-resolution display like that of the Macintosh, even if it wasn’t in color.

Putting the “Power of the Printed Word” Within Reach of Everyone

Wendy Woods presented her first remote report, narrating some B-roll footage taken at Highlights Electronic Publishing Company, a desktop publishing shop in Oakland, California. Woods said the successful wedding of computers, lasers, and printers was on the verge of transforming traditional publishing and printing at every level. For the small business, DTP meant having near total control over the design and printing of small documents.

At Highlights, Woods said, owner George Poor combined electronic communications with desktop printing to provide a complete, self-contained newsletter publishing service. His clients spanned the globe, from a local nursing association to trans-Pacific teleconferences. DTP created a new category of printing professionals like Poor, who could take an unproofed memo from halfway around the world, strip off the original formatting, and clean up the document like an ordinary word processing job. Then using a program like PageMaker, he composed the layout of the document from text to tiles to graphics–all on his Macintosh. The final step was the printing, usually done on the spot with a LaserWriter.

Woods said that while the impact of electronic publishing had just begun in the professional world, it was easy to see its appeal to individual publishers. DTP was relatively inexpensive and fast. It used common hardware. And the print quality, while not yet up to photo typesetting, was fine for smaller jobs. But best of all, DTP put the power of the printed word within reach of everyone.

This Episode Was Brought to You by the Letter “B”

Michael Tchong and Richard A. Ware joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first studio round table. Tchong was vice president of marketing with Manhattan Graphics Corporation. Ware was a font designer with CasadyWare.

Kildall opened by asking Tchong what DTP offered the average Macintosh customer. Tchong said it offered a significant cost savings and something that was previously not achievable using software like spreadsheets and databases. He said there were studies that showed people could save as much as 50 percent.

Kildall asked about the specific uses of DTP. Tchong said newsletters were the most common application. But he expected that would change as people realized the power of DTP to prepare other types of documents such as memos and letters.

Cheifet followed up on the cost savings claim, clarifying that was compared to taking a printing job to an outside printing house. Tchong said that was correct. He added that people were also now starting to produce documents using DTP that would have previously just been typewritten.

Kildall asked Tchong to demonstrate his country’s DTP program Ready, Set, Go! (I’ll just refer to it as RSG.) RSG was page layout software. Tchong started the demo with a new, blank document. He created a text block. He said RSG allowed for free-form design, so the user could place pictures anywhere they liked in combination with text columns. Text could be typed in directly or brought into the program. RSG supported multi-column layout so text “automatically flowed” from one column into the next. There was also an optional grid that helped the user line up their text columns and graphics. Tchong then demonstrated how to add a graphic to a document as well as how to change the font size.

Cheifet noted this was the third version of RSG that Manhattan Graphics had published for the Macintosh. What was new about this version? Tchong said the initial product lacked the typographic features that customers wanted. The new version had those features, such as kerning and hyphenation. Cheifet asked what “kerning” was. Tchong said it was simply the ability to move letters closer together. For example, if you had a “t” and a “y,” the “y” was tucked under the “t.”

Cheifet asked Tchong to show a sample document created with RSG and printed on an Apple LaserWriter. Tchong handed Kildall a sample “Memo.”

Cheifet then turned to Ware and asked him why fonts were important. Why did you need a choice of different fonts? Ware said fonts communicated more than just the words–it communicated the feeling. Fonts gave particular words more impact. It could communicate a formal or informal feeling.

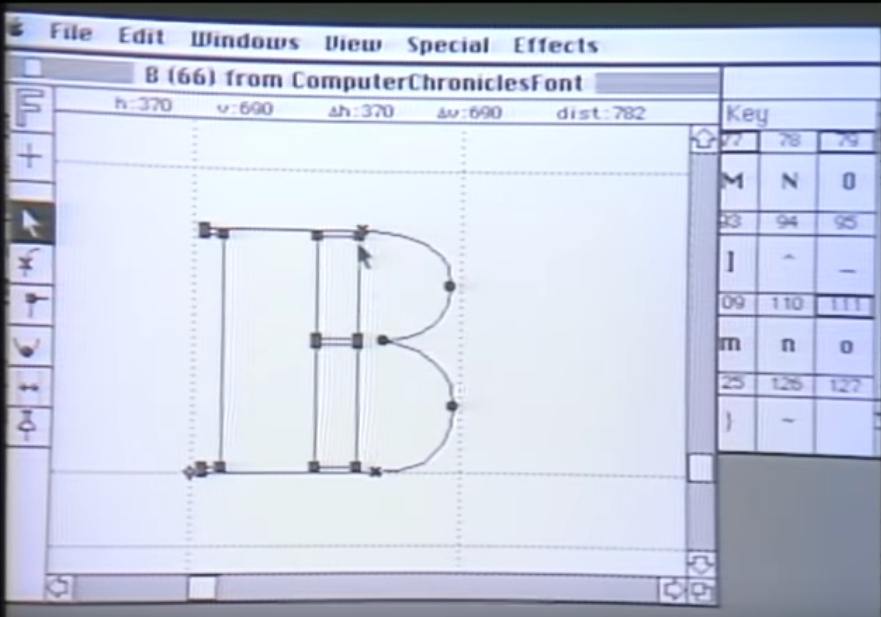

Cheifet noted that Ware designed fonts using a program called Fontographer. How did Ware actually create a font? Ware explained that with Fontographer he created the outline of the font and the outline description, which was then translated into the PostScript language used by the LaserWriter. Cheifet clarified that Ware made custom fonts as opposed to buying an existing font package. Ware said yes, he made the fonts from the “ground up” and sold them as a product.

Ware then provided a demonstration of Fontographer. There was a grid displaying all of the possible character locations. By default this grid showed the Macintosh system font. He selected one of the characters–the “B”–and a separate window appeared showing the points and paths that made up the letter (see image below). You could then zoom in up to four levels and manipulate the individual points. Each of these points had a pair of Bezier control points, which could be used to alter the curved lines within the character.

Kildall asked Ware what he looked for when designing a font. How did you make it all look the same? Ware said it was an art form. You had to make sure that when you read a page of text, you didn’t have some parts looking “heavy.” There was lots of tradition behind font design but it was still possible to be creative.

Giving the Mac a Properly Sized Display

Michael Boich and Randy Kincaid joined Cheifet and Kildall for the next round table. Boich was president of Radius, Inc. Kincaid was a manager with Dynamic Graphics, Inc.

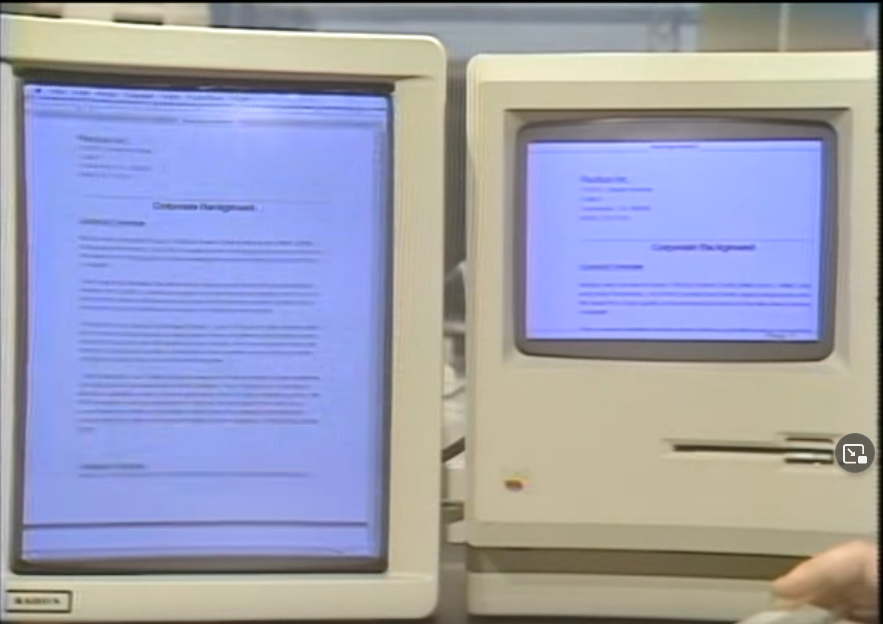

Boich was there to demonstrate the Radius Full Page Display, an external monitor for the Macintosh. Kildall quipped it was a great product for people like him who lacked 20/20 vision and couldn’t read the tiny Macintosh screen. Boich presented his demo using a word processing program called WriteNow. He first showed a sample document on the built-in Macintosh screen, which only displayed about one-third of an 8.5-by-11-inch page. He then opened a second copy of the same document on the Radius display, which showed the entire page (see image below).

Kildall asked about the resolution of the Radius display. Boich said it was identical in dots-per-inch to the original Macintosh display. But in terms of total pixels it was 640-by-864. For comparison, the Macintosh display was 512-by-342 pixels. So the Radius offered about triple the area of the built-in display.

Cheifet noted that you could work with both the built-in and Radius displays at once. Boich showed how you could move the Macintosh cursor “across” the screens seamlessly. You could also span a single window across the two displays. Boich said a more common use of the two-display setup was to work on a document on the Radius while using an accessory or tool on the built-in display.

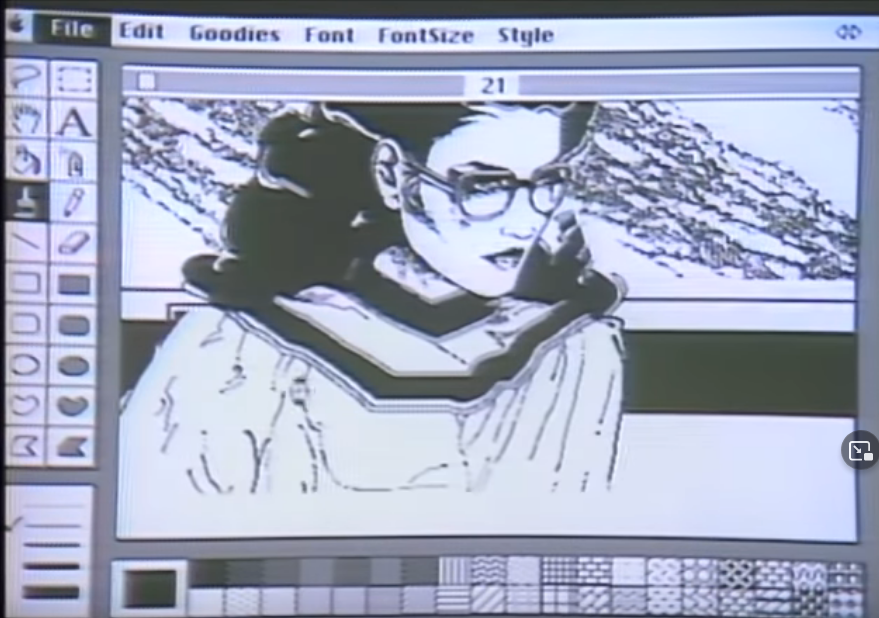

Cheifet turned to Kincaid and asked about his company’s product, DeskTop Art. Kincaid said DeskTop Art was “art for everyone who’s not an illustrator.” It contained the work of professional illustrators stored on software. (In other words, it was a bunch of clip art disks.) So instead of buying a paper volume of clip art that you had to cut out using scissors, you could use clip art provided on a disk.

Kincaid demonstrated DeskTop Art using MacPaint. DeskTop art came with a printed index of images, which showed the specific folder locations of each image on the program disks. So you looked for the image you wanted in the index and then went to the corresponding folder number. For his demo, Kincaid picked an image of a woman in glasses, or what he described as a “very pretty teacher” (see image below).

Kildall asked Kincaid how you actually brought the image into a document. Kincaid said all of the page composition software for the Macintosh–including PageMaker and the previously demoed Ready, Set, Go!–could import these images, which were in the Macintosh PICT format. So you could easily import any of the images just by pressing a couple of buttons.

Kildall asked if it was possible to scale an image, for example to make it smaller. Kincaid said that was difficult to do with DeskTop Art since these were bitmap images. But many of the page composition programs were capable of doing some scaling. Chiefet asked if you could actually edit or manipulate images with DeskTop Art. Kincaid said yes, you could invert or flip an image.

Kincaid then pulled up another sample file from WordArt using MacDraw. In this case, it was a sheet containing several clip art images. Kincaid copied one of the images–a girl reading a book–and pasted it into a new document. He also showed that you could modify the image by breaking it down into the individual objects used to create the illustration in the first place.

Chevron Moves Internal Newsletter to DTP

Wendy Woods returned for her second and final remote segment, this time from Chevron Corporation in San Ramon, California. Woods said the biggest test of desktop publishing was taking place in corporate offices like this one. Here, the company’s personal computing services center used a small network of Macintoshes running PageMaker, a LaserWriter, and an IBM PC-AT as a file server. With this setup, Woods said the center produced Pacer, a newsletter about personal computing that went out to 3,500 Chevron employees.

One year earlier, Woods said, Pacer was still being made with a mainframe editor and without the benefit of the versatile fonts and graphics of the LaserWriter. The process used to take 6 to 8 weeks. Mary Neff, a Chevron employee, told Woods that when desktop publishing came out, they were able to finally merge text and graphics and explain some very complicated technical issues to her readers. This led to an increase in readership. Neff added the turnaround time for producing a document was also much quicker with DTP. She could put out a draft copy, get the changes back, edit them, and get the newsletter out within a one-month lead time.

Woods said the DTP system gave the Chevron staff more control over their finished product and plenty of praise for its format and style. The center had only been using the system for only about a year but already it was considered an overwhelming success–so much so that other offices within Chevron and even other Fortune 500 companies had been calling to ask for help in setting up their own DTP system.

PageMaker Users Had a List of Demands

Paul Brainerd, the president of Aldus Corporation, was the final guest for this episode. Stewart Cheifet noted that Brainerd invented the term “desktop publishing” and developed PageMaker. Kildall asked how far back did DTP actually go. Brainerd said we were only talking about a year to 18 months.

Kildall asked about the beginnings of DTP. Brainerd said his background was in the publishing business, specifically newspapers and journalism. He saw that it was possible to take microcomputers and combine them with laser printing technology and software like PageMaker to produce a solution for people who wouldn’t have had access to these tools before.

Kildall wondered if DTP was an actual substitute for manual typesetting or just a replacement for a typewriter. Brainerd said it was both. DTP offered a more professional result than what word processing could do alone. It might be short of what you needed to produce a book or a magazine, but it could do everything in-between

Cheifet brought up the Steve Jobs quote that I referenced earlier. He characterized Jobs as claiming that DTP would just evolve into “one big fancy word processor.” Did Brainerd think that would happen? Not necessarily, Brainerd replied. He said in the long-term that word processing would fully integrate text and graphics. But there would be a wide range of products available as not everyone needed the ability to combine text and graphics.

Kildall asked about what was missing from current DTP packages. What were people asking for? Brainerd said that Aldus had a running list of user requests and there currently contained 270 items. Users wanted more typographic capabilities, hyphenation support, kerning, and larger page sizes, just to name a few things. Cheifet noted that PageMaker recently released its 2.0 update for the Macintosh. What new features were added? Brainerd said it covered the items he just mentioned.

BBS Users Fight Trojan Horses

Stewart Cheifet presented this episode’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in October 1986.

- Bulletin board users were starting to take action against “cracked hackers” who planted “Trojan horse” software on systems.

- Lotus announced its new word processing program Manuscript.

- IBM announced its own brand of desktop publishing software for the IBM RT PC.

- Hayes Microcomputer Products introduced new versions of its Smartmodem and Smartcom II modems for the IBM PC Convertible.

- The Reader’s Digest Association was reportedly exploring a sale of its online service, The Source.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Get! (Signet Technologies, $89), a program that automatically checked electronic mail services at specific times or intervals.

- IBM, Commodore, and Sony were among the major western companies buying more software from Communist-controlled Hungary.

- Mississippi farmers were testing two new software programs designed to measure variables such as weather conditions and plant growth. Cheifet said that one cotton farmer was able to double his crop output per acre using the software.

- Texas A&M University was the first school to adopt an “online” class registration system that allowed students to select their courses by using their touch-tone phones.

- The ENIAC recently celebrated its 40th anniversary.

Boich Ran the Personal Computing Triathlon

Michael Boich started his tech career at Apple. Indeed, he was part of the team at Apple that originally developed the Macintosh. He is often credited as Apple’s first “software evangelist,” i.e., someone charged with aggressively marketing the Mac to third-party developers. In that role, Boich helped forged the early relationship between Microsoft and Apple, with the former developing Excel and Word among other programs for the original Macintosh.

Boich later expressed frustration with Apple’s decision to sue Microsoft over allegations that Windows infringed on copyrights Apple claimed for the Macintosh operating system. In an April 1988 interview with Laurie Flynn of InfoWorld, Boich said the lawsuit was “probably not worth it.” He also shared this telling anecdote of a confrontation between the public faces of the two budding tech giants:

My favorite story was about being in this meeting one time when Steve Jobs was complaining about the Windows development Microsoft was doing because they were still working on Mac stuff and nondisclosed on things. Apple’s programmers thought Apple was giving away the store by letting Microsoft have Macs. To this [Microsoft chairman] Bill Gates said that the Windows people don’t get to see the Mac stuff, that they’re different programmers from the Windows developers.

Steve insisted that wasn’t the point. He said it was more like if Bill’s big brother punched Steve’s big brother in the nose, people would say the Gateses were beating up on the Jobses.

To this Bill said: “No, Steve, it’s kind of like if we had rich neighbors named Xerox, and I went in to steal their TV set, and you said, ‘Hey that’s not fair, I wanted to steal that set.’”

In 1986, Boich and three of his colleagues left Apple to start Radius Inc. Radius’ first two products were the Radius Accelerator, a Macintosh expansion board that added a second microprocessor; and the Radius Full Page Display that Boich demonstrated in the episode, which originally retailed for $2,000. These products were successful in the hi-end market and Radius continued to develop a variety of Macintosh-related products through the early 1990s.

Boich took Radius public in 1990, served as CEO until 1994, and stayed on as chairman until 2000. In 1995, Radius became the first company to manufacture an Apple-licensed Macintosh clone. But as Luke Dormehl noted in an article for Cult of Mac earlier this year, the deal didn’t really work out for either company:

As per the deal Radius signed, the clone-maker only paid Apple $50 per machine produced. Apple thought the clones would increase Mac market share. However, the strategy actually cost Cupertino money. It stopped people from buying Macs directly from Apple, without enlarging the size of the overall pie.

Radius stopped making the System 100 computer in January 1996. The company then sold its Mac license to Taiwanese scanner manufacturer Umax Data Systems in May. The following year, when Steve Jobs returned to Apple and began to turn the company in the right direction, he pulled the plug on clone Macs.

Despite the clone failure, Radius continued to chug along as a manufacturer of high-end video production tools. In 1999, the company changed its name to Digital Origin Inc. Three years later, in January 2002, Media 100 purchased Digital Origin in an all-stock deal valued at $83 million. This turned out to be part of an ill-fated buying spree by Media 100, which filed for bankruptcy a year later.

As for Boich, he followed up his tenure at Radius by co-founding another startup, Rendition, Inc. Abandoning Boich’s Apple roots, Rendition focused on developing a 3D graphics engine for the PC platform. After a three-year tenure as CEO, Boich sold Rendition to semiconductor giant Micron Technology in September 1988 in an $88 million all-stock deal.

Boich’s next startup was Eazel, Inc., which he co-founded in 1999 with former Apple and Radius colleagues Bart Decrem and Andy Hertzfeld. Completing Boich’s personal computing triathlon, Eazel tried to develop a Linux user interface for the consumer market. That didn’t last long. Eazel closed up shop in January 2002 after just 16 months. That said, Eazel’s legacy continued in the form of Nautilus, a graphical file manager designed by Hertzfeld, which continues to be part of the Linux GNOME desktop today.

Eazel was Boich’s last CEO gig. During the 2000s he did the usual corporate board and venture capital gigs. His last known position was as a board member at Federspiel Controls Inc., now known as Vigilent, a company that develops HVAC control systems. (Mark Housley, who previously served as CEO of Radius/Digital Origin, is Vigilent’s current chairman and CEO.)

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of October 16, 1986.

- Richard Ware designed fonts for a company known in 1986 as CasadyWare, Inc. Robin Casady started the business in 1984 specifically to develop downloadable PostScript fonts for the Macintosh. He formally incorporated the business as CasadyWare in November 1986 just after this episode aired. In March 1989, CasadyWare merged with J. Michael Greene’s Greene Software Inc. to form Casady & Greene, Inc., which continued to operate as a general software publisher for Apple’s platforms until July 2003.

- The program that Ware demonstrated, Fontographer, was originally developed by Altsys Corporation. Macromedia, Inc., acquired Altsys in 1995 and continued to update and release Fontographer. FontLab Ltd. subsequently acquired the program’s rights from Macromedia after Adobe Systems bought the latter in 2005. FontLab produces its own font editing software, also called FontLab, but continued to publish Fontographer up through the release of version 5.2 in 2012.

- Ready, Set, Go! (RSG) was first published by Manhattan Graphics Corporation in 1985. It was positioned as a lower-cost alternative to PageMaker, with the 3.0 version demonstrated on Chronicles initially retailing for $295 in late 1986 versus $495 for the Aldus product. Manhattan Graphics subsequently sold RSG’s publishing rights to Esselte LetraSet, an office and graphics arts supplies company, in 1987. Esselte split the product into two lines, a $300 RSG and an $800 program called DesignStudio. Manhattan Graphics reacquired the rights to the lower-end RSG in 1992 but by then the product had lost too much ground in the market. Esselte subsequently sold its rights in DesignStudio to Diwan Software Limited in 1996. Diwan, a London-based company, continues to sell a Windows version called Ready, Set, Go! Ruby and an Arabic-language counterpart called al-Nashir al-Sahafi Yaqout

- Michael Tchong followed up his work at Manhattan Graphics by starting MacWEEK magazine in 1987. Short of cash, Tchong sold 50 percent of the magazine to publishing giant Ziff-Davis a year later. He eventually left MacWEEK altogether in 1991 after feuding with Ziff management, according to a 1994 Wired article. In the 1990s, Tchong founded Atelier Systems, a communications software company, and ICONOCAST, an Internet marketing company, both of which he quickly sold. Today he promotes himself as a “futurist” and public speaker.

- Paul Brainerd was also a guest on the next episode I’ll be reviewing, so I’ll delve more into him and PageMaker at that time.

- As I discussed in a previous post, the Reader’s Digest Association did eventually sell The Source, although that did not actually take place until March 1989, when it was bought by CompuServe. (Wendy Woods’ Newsbytes, which I cited in my introduction, was published on The Source during this time period.)

- For the record, neither Steve Jobs nor Bill Gates have any brothers, although they each have two sisters.