Computer Chronicles Revisited 74 — Venture's Business Simulator, PC Type Right, the Toy Shop, and Thomas M. Disch's Amnesia

The second annual buyer’s guide episode of Computer Chronicles aired in early December 1986. Although the Intel 80386-based PCs were the hot items coming out of COMDEX a few weeks earlier, the Chronicles gang chose to focus their gift-giving ideas on the software and small-scale hardware side of the computer industry.

On that note, Stewart Cheifet opened the program by showing George Morrow–sitting in for Gary Kildall for the second week in a row–the Selectronics PD-100, a credit card-sized computer with a keypad and 2 KB of memory that functioned as a “personal directory.” Cheifet demonstrated how you could use it to keep a Christmas shopping list. Morrow retorted, “How long did it take you to put all that [information] in there, Stewart?” Cheifet laughingly replied it didn’t matter since he had a “lot of fun” playing with the device.

More seriously, Cheifet said the Christmas shopping season was very important to lots of businesses such as department stores. How important was it to the computer industry? Morrow said this year it would be a little more important than usual due to the looming changes to the federal tax code. (The United States Congress adopted a major Tax Reform Act in 1986.) This meant that a lot of people would be spending money at the end of this year to buy computer equipment that they might not have otherwise. On the lighter side, Morrow said that “hope beats eternal” in the computer industry each Christmas someone will find a product that succeeds in the home market.

Assemble the Usual Suspects

Computer Chronicles regulars Wendy Woods and Paul Schindler were the sole “guests” for this episode. As was established in the prior Christmas buyer’s guide program, these next two segments were “round robins” where each panelist presented ideas for computer-related holiday gifts.

Venture Business Simulator

Cheifet went first, demonstrating Venture’s Business Simulator, which he said was developed by people who taught at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. He said this $99 disk contained a series of business case studies actually used at the school. And much like Flight Simulator allowed you to simulate flying and crashing a plane without hurting anyone, you could use Business Simulator to simulate running and “crashing” a business without actually going bankrupt. (Morrow joked he should have gotten this program based on his own company’s recent demise.)

Cheifet explained that Business Simulator provided a number of informational screens in the forms of annual reports, “newspaper” articles, and even memos from company executives. The player could then make decisions regarding the business, such as how to price your product, how much to spend on advertising, whether to expand manufacturing capacity, and so forth. The program then processed those decisions and simulated the business for one year.

Morrow asked if this was “true simulation.” Cheifet said it was based on six real case studies used to teach MBA students. Reality Technologies, the company behind the product, also said it could make “custom” case studies tailored to a particular business or product.

Norton Utilities 3.1

Morrow went next and recommended Norton Utilities 3.1. He noted the program had “saved my life twice this year.” He elaborated that he had a 12 MB database to keep track of his record collection. The database was corrupted somehow and Norton helped him recover the data. Otherwise, it would have taken him over a month programming in assembly language to get his files.

Schindler chimed in that one key feature of Norton was an “unerase” function that you could use to recover previously deleted files. Morrow added that there were other programs on the market that provide unerase functionality. But Norton was the only one that he knew of where the user could go in and “fiddle” with a file if necessary.

Xerox PC Type Right

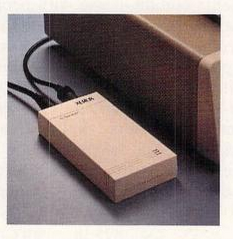

Cheifet turned to Woods and asked her to explain the “mysterious white box” that she brought. Woods said it was the PC Type Right, a hardware-based spelling checker made by Xerox. She said that anyone who used a traditional spell checker program knew how much memory it took up, so by the time you got to your document there was very little RAM left.

The Type Right was separate from the computer. You plugged a cable from the Type Right into the keyboard port on a PC, and then plugged the cable from a detachable keyboard into the Type Right. The unit would then monitor the user’s typing and beep when a word was misspelled. Woods said the device had a 100,000-word vocabulary and could be customized to add about 1,200 additional words. Cheifet asked about the price. Woods said it sold for about $200. Xerox had just announced this product at the November COMDEX show, so it was still getting out onto store shelves. She added the $200 price was about what you would pay for a good software-based spelling checker.

Schindler said he thought the Type Right was a “fantastic idea.” He also needled Morrow because he apparently didn’t care much for spelling checkers. Morrow replied that he never used to like spelling checkers but he was now using one. It helped him go from spelling about 60 percent of his words right to over 95 percent. (Morrow pointed out that he never passed a high school English course.)

A Couple of Books and Looking Your Best

Schindler began his turn by recommending a pair of books. The first was The IBM XT Clone Buyer’s Guide by Edwin Rutsch. Morrow quipped that this was probably the only book on the face of the Earth that was out-of-date 10 minutes after it went to press. Schindler conceded the point but said the book offered general advice on what to look for when buying a computer. (According to the Whole Earth Review, the self-published book was actually updated monthly, presumably to account for new machines.)

The second book Schindler recommended was More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Hard Disks for the IBM PC by Robert E. Brown, who was himself a Chronicles guest back in December 1985. Schindler noted–and Morrow concurred–that not all hard disks were created the same. They had different access times, different prices, and different capacities. (And, Morrow added, different things that could go wrong with them.) Brown’s book offered a thorough examination of every hard drive available on the market. Morrow said every computer user group should have a copy. Schindler agreed.

Schindler then turned to a brief software demonstration of a $35 program called Looking Your Best by 1 Step Software. Schindler said the program was a “clothing adviser.” The user could input information about their body type and shape and the software would provide advice on how to “dress for success.” (For some reason, Schindler demonstrated the “female” version of the program, although there was also a “male” version available.)

Would “Flashy Newcomers” Attract Home Computer Buyers?

Wendy Woods presented a single remote segment from Winner’s Circle Systems, a Berkeley, California, computer store. She said that December was here, and once again, computer owners were faced with a surging need to buy, much to the pleasure of computer retailers. Some computer owners were ready to upgrade their systems, while others simply wanted accessories or gifts for their computer-savvy friends.

Whatever the motivation, Woods said, sales were climbing and retailers were optimistic. Andy Jung, the manager of Winner’s Circle Systems, said his store’s sales had actually improved over last year. Sales going into Christmas last year were very high, and this year they were running about four times higher.

Woods said that many shops prepared for Christmas by increasing their stock of high-priced luxury goods. But computer vendors were in the awkward position of balancing sales between corporate buyers and a growing consumer market that was also becoming more sophisticated. Jung said that in the past, people were looking for systems under $500. The average consumer now was budgeting between $1,500 and $2,000 for a computer purchase, which matched the inventory he kept in the store.

Woods noted that this year’s “flashy newcomers” like the Amiga, the Atari ST, and the hard-to-get Apple IIgs provided attractive floor demonstrations in the store. But they may not have the lasting impact of lower-priced and more powerful machines. Jung explained that back in 1979, there wasn’t the same variety of computers available. An Apple II with 16 KB of RAM sold for $3,500 back then. Today you get an Apple IIc with 128 KB for under $1,000.

The HP Business Consultant

The panel returned for a second round robin. Cheifet opened by showing Morrow the Hewlett Packard HP-18C Business Consultant, which was something of a pocket computer-calculator hybrid. The device had six user-defined function keys that could store formulas. For example, Cheifet created a formula to calculate the cost of renting a car. He then showed how you could send calculations from the Business Consultant to a small printer via an infrared connection.

The Muppet Learning Keys Keyboard

Cheifet had one more product to show, this one targeted at kids: The Muppet Learning Keys keyboard by Sunburst Communications. It was designed to help little kids get comfortable with using a computer. Instead of a QWERTY-layout, the keyboard was presented in an A-Z format to help children learn the alphabet. Cheifet demonstrated some educational software that came included with the keyboard. Pressing a letter such as “H” would bring up an item whose name started with said letter, in this case an anthropomorphic hamburger. And pressing the number “3” brought up three pictures of the same hamburger.

Morrow asked how the keyboard connected to the computer, which in this case was an Apple IIe. Cheifet said it plugged into the Apple’s joystick port. He added that the keyboard replaced a lot of the traditional function keys with pictures that were easier for a child to understand. For instance, instead of ENTER there was an image of Kermit the Frog on a motorcycle with the word “GO”.

SAT Prep Software

Morrow, continuing his utilitarian approach to gift-giving, recommended Barron’s Computer Study Program for the S.A.T. He noted the package came with 6 to 8 disks. The program provided information on how to study for the test and how much time to spend on questions. He noted the SAT was getting to the point where they were like the entrance exams used by Japanese universities. So there was greater pressure to pass, and he thought that the software offered better prep than a traditional book.

The Toy Shop and the Kurta Pen Mouse

Schindler–along with models of a catapult, carousel, and car–went next. The models were made with what Schindler called “the hot computer toy” for this Christmas season, The Toy Shop by Brøderbund Software. Schindler explained that the paper plans for all the toys displayed came from this program. He showed how the toys actually “worked,” e.g., the carousel actually turned, the catapult fired spit wads, et cetera.

Schindler noted that Brøderbund actually provided these finished models for the studio demonstration. But he’d already made some models himself at home and planned to make several more. He said Toy Shop was a great project for a parent to do with their kids. You could also personalize the models by putting in a child’s name or changing the patterns. Morrow said the appeal of this type of program was that it let you put something together after the computer did its work. Cheifet observed that Toy Shop was basically a “mini-CAD” program. Schindler agreed, adding that once the computer printed out the basic parts for the model you added other items such as wood and glue.

Schindler also briefly demonstrated the Kurta Pen Mouse, yet another product recently unveiled at COMDEX. For “people who don’t like mice,” as he put it, this device was a $300 electronic pen that moved across a pad, which in turn moved a cursor across the computer screen. Schindler said it took about an hour or two to set the device up, which was why there wasn’t time to do an actual studio demonstration. Cheifet noted the device was similar to a Koala Pad. Morrow cautioned that the Pen Mouse contained a small radio transmitter, so if you got close to another RF source like a television or radio signal there could be interference.

Thomas M. Disch’s Amnesia (and a Chocolate Floppy)

Woods provided the final product demo for the episode, a text adventure game published by Electronic Arts called Thomas M. Disch’s Amnesia. She explained the setup of the game: The player woke up without any clothes in a hotel room. The player had amnesia and needed to figure out where they were, how to get clothes, and so forth. Schindler interjected to say that all the games from Electronic Arts were great. He didn’t want to give any company a “blanket endorsement,” but he “never played a bummer from these guys.”

Woods described the game as “fascinating” and that everyone who had played the game at her house had enjoyed the experience. Amnesia was set in Manhattan and came with a map of the local subway system, which was programmed into the disks. There was also a cross-street indicator (a code wheel) and a telephone directory included as part of the documentation. Morrow asked if Amnesia always had the same outcome. Woods said no. She’d played the game 5 or 6 times and found a number of different endings.

Finally, Woods recommended a novelty gift called “The Chocolate Byte,” a 5.25-inch floppy disk made out of chocolate that was only available during the holiday season.

What Would IBM Do in 1987?

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in December 1986.

- Rumors were still building about IBM’s plans for 1987, including the unveiling of the PC-2, which was expected to be a $1,000 PC with 3.5-inch disk drives and a modified Intel 8086 chip. Cheifet said analysts expected a new flood of software to take advantage of the PC-2 design–software that would not run on PC clones.

- It was also rumored that IBM would unveil the PC-2 in a Super Bowl commercial. Cheifet said that Apple might also use a Super Bowl ad to announce a PC-compatible machine.

- Other predictions for 1987 included IBM releasing a 386 machine and an upgraded PC convertible.

- Ashton-Tate announced it would come out with “subsets” of its dBase III program for 386 computers. Cheifet said Ashton-Tate would “unbundle” dBase so the program’s separate modules could take better advantage of the 386 chip’s power.

- Commodore said its Quantum Link was now the second-biggest online service after CompuServe. Cheifet noted that Quantum Link currently only worked with Commodore machines, but that the service would be opened up to IBM and Apple users sometime in 1987.

- Two Pennsylvania doctors said a “lack of circulation” in the thighs of computer users could lead to blood clots.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Perspective (3D Graphics, $300), a program for making monochrome three-dimensional graphs.

- BusinessWeek predicted a good holiday season for software sales, with Brøderbund’s The Print Shop and Infocom’s Leather Goddesses of Phobos expected to do well.

- Syndicated computer columnist John C. Dvorak recommended a Macintosh game called Smash Hit Racquetball and Borland’s Traveling SideKick for the PC, as well as the Beck-Tech’s Fanny Mac (a cooling fan for the Macintosh) and the Curtis Computer Tool Kit.

- Family Computing’s annual shopping guide named the Atari 1040ST ($999) and Tandy Model 102 portable ($499) as “Best Deals,” the Toshiba P-321 ($699) as the “Best Printer,” the NEC MultiSync Monitor ($899) as the “Best Monitor,” and the Leading Edge Model L ($149) as the “Best Modem.”

- WGBH, the public television station in Boston, planned to conduct the world’s first “online auction” in February 1987 as a fundraiser.

EA’s Growing Pains as a Publisher and Distributor

Paul Schindler’s ringing endorsement of Electronic Arts as a company may sound ridiculous to people today who complain about EA’s approach to developing games–especially in light of the recent backlash to Madden 23–but as with all such statements, context is key. The EA of 1986 was still very much a start-up firm. Two-time Chronicles guest Trip Hawkins started EA in 1982, shipped the company’s first games in 1983, and didn’t take the company public until 1989.

During this early period EA was also primarily a publisher, not a developer. EA’s producers acquired most of the company’s games from third-party sources. That was true of not just Thomas M. Disch’s Amnesia, but also Venture’s Business Simulator, two of the products recommended in this episode.

Business Simulator might sound like an odd fit for EA, but again, this was not the modern game studio with blockbuster franchises like Madden and The Sims. (Madden actually was in development for the Apple II in 1986, but EA did not release the finished product until 1989.) Like many early computer game publishers, EA put out a lot of programs that were not strictly “games” in order to survive the mid-1980s decline of the original home computer market. This was how you got something like Business Simulator, which targeted a professional audience who might be willing to pay $100 for a piece of software.

Stewart Cheifet’s description suggested that Business Simulator came out of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. That’s indirectly true. Two Penn graduates, Mark Goldstein and Doug Alexander, started a company called Reality Technologies, which developed Business Simulator as a PC adaptation of software they had used on a DEC minicomputer while at Wharton. Reality signed an “affiliated label” agreement with EA in April 1986, which basically meant that EA handled distribution while Reality absorbed most of the actual publishing costs. Reality also had an endorsement deal in place with Venture magazine, which is why EA distributed the finished program under the name Venture’s Business Simulator.

As EA and Reality were both private companies at the time, it’s difficult to know how well Business Simulator sold. Reality itself went on to be a moderately successful company, mostly developing and licensing online investment software. In 1994, Goldstein and his partners sold the company to Reuters for $13.7 million.

Amnesia Proved a (Mostly) Forgettable Game

Thomas M. Disch’s Amnesia was also a departure from the normal late 1980s EA fare. Although Amnesia was definitely a game, it was a text adventure, which EA had no prior experience publishing. Indeed, Amnesia would end up as the company’s only foray into this market and was by some accounts the only Electronic Arts game released without a single on-screen graphic.

Amnesia did not start out at EA. The story behind this game has already been well documented by several others, including Jimmy Maher and Aaron A. Reed, so I’ll try and keep this overview succinct.

The developer behind Amnesia was Cognetics Corporation, a company founded by Charlie Kreitzberg in 1982. Kreitzberg provided his own account of Amnesia’s creation in a 2019 interview with John Aycock, a computer science professor at the University of Calgary. Prior to Cognetics, Kreitzberg told Aycock that he’d worked as a programmer with the Educational Testing Service in New Jersey. With that background in standardized testing, Cognetics’ first project was developing an SAT preparation program for Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. (Ironically, this was a different SAT prep program than the one George Morrow recommended.)

As it turned out, an editor that Kreitzberg worked with at Harcourt later moved to another publisher, Harper & Row, which was also looking to enter the test prep software market. This editor introduced Kreitzberg to Jane Irsay, who ran Harper’s software unit. Irsay, in turn, introduced Kreitzberg to science fiction author Thomas M. Disch.

During the mid-1980s there was a brief period where a number of traditional book publishers, including Harper and Row, sought to publish Infocom-style text adventure games with prose written by traditional authors. Perhaps the most famous example of this so-called bookware was Douglas Addams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which Infocom itself released in 1984. Thomas M. Disch was, like Addams, an established author, though not as commercially successful. (Jimmy Maher described Disch’s work as “uncompromisingly bleak,” which I’m guessing contributed to that lack of success.) And Disch was apparently eager to try his hand at writing a text-based computer game.

It turned out that Kreitzberg was also interested in this market. A Cognetics programmer, James Terry, developed a Forth-based text adventure engine dubbed the “King Edward language.” (Kreitzberg said the name came from a brand of cigars.) Disch then wrote a 450-page script for what became Amnesia, which Terry and another programmer, Kevin Bentley, then translated into the King Edward language.

As Kreitzberg recalled to Aycock, the development was quite difficult, as it was done entirely on an Apple II using 5.25-inch floppy disks and no hard drive:

Compiling the game took more than a day. The computer ran so hot that we purchased a large fan and pointed it at the open case. Every time we did a compile, we prayed that the equipment would keep working long enough to get us to an executable.

Another challenge was that midway through development, Harper and Row decided it didn’t want to be in the software business after all and abandoned Amnesia. It was at that point that a producer at Electronic Arts, Don Daglow, decided to pick up and publish the game.

Daglow gave his own account of Amnesia to Gunnar Lot of the German podcast Stay Forever in 2018. Daglow himself had a long history of developing computer games for 1970s mainframes and early video games for the Mattel Intellivision. After Mattel exited the market in the wake of the 1983-1984 video game crash, Daglow ended up at EA as a producer.

Daglow was, by his own admission, an enormous fan of Disch’s literary work. So when he learned that Amnesia was in limbo, he signed a deal with Cognetics to have EA take over the publishing. Daglow said he faced some initial resistance from EA management over the proposed size of the game. Executing Disch’s original script would have required shipping the game on six 5.25-inch floppy disks, Daglow told Lot. But EA never shipped a game with more than two disks, which Daglow conceded made financial sense given the size of the company at the time:

[T]he EA that we’re talking about then is not the EA we have now. All of our employees sat in a single office in San Mateo, California. I think when I joined EA, there were about 40+ people, maybe 43 people in Electronic Arts. When I signed [Amnesia], probably we had 65. We were not a big publisher that had a big bank account. Every game we published was a significant risk. And the price points we could charge were pretty well defined.

Even pared down to a 2-disk release, Daglow said Amnesia “did not do great” in terms of sales. For his part, Kreitzberg recalled the game “did moderately well” but admitted it “was not that blockbuster that we, Tom [Disch], and Electronic Arts hoped for.” Again, I’m not aware of any exact EA sales figures from this period, but the company had several best-selling releases in 1986–such as The Bard’s Tale II and Starflight–and Amnesia has never been considered in a class with those games.

Yet Wendy Woods’ praise suggested this could have been a successful game. What went wrong? Kreitzberg and Baglow both cited the technological limitations of the time. Echoing Daglow’s struggles to get the game on six disks, Kreitzberg acknowledged that Disch’s script “was probably too sophisticated for the computers available.” There was also the fact that the adventure game market had shifted away from pure text and towards graphically animated games like Sierra Online’s King’s Quest.

But Amnesia itself also quickly developed a reputation as something of a slog to play. Scorpia, the pen name for a well-known computer games reviewer of the time, wrote in the January-February 1987 issue of Computer Gaming World that Amnesia “begins with a fascinating premise, then falters in the execution of it.” She cited the fact the game often forced you into a single path of decision-making in order for Disch’s plot to reach its scripted conclusion. Then there were “further annoyances” created by what amounted to a primitive life simulator once the player got out of the starting hotel room and out onto the streets of Manhattan:

Your character has an energy level, which tends to drop rapidly if you don’t eat something. You can only move around a few hours (game time), before being warned that you need to rest. At that point, you must eat something soon (if you have the money), or nip back to the tenement and sleep awhile. The difficulty is that a reasonably healthy adult male should be able to go most of the day without having to eat something. You have to be pretty frail to collapse if you don’t have your morning Wheaties. But that’s what will happen eventually.

Wendy Woods mentioned the telephone book, subway map, and cross-streets code wheel that came with Amnesia. These too ended up being “further annoyances” for many players. Scorpia noted that you needed the telephone book to make calls from a payphone at 25 cents a pop–thus creating an additional need to earn money in the game by panhandling or performing other menial work. You also needed that money to ride the subway. As for the code wheel, that was simply copy protection, as Kreitzberg readily admitted in his interview with Aycock. And that wasn’t a one-time thing. While on the streets in-game, the player would receive repeated requests to look up cross streets.

Daglow explained that Disch always intended for the player to spend most of the middle of the game struggling to survive in Manhattan. He said Amnesia was essentially a three-act game. The first and third acts were a “traditional text adventure,” while he described the middle act as a “sandbox game.” While Daglow pushed back at the suggestion from Gunnar Lot that this middle portion was “unfair,” he admitted “we could have used three more months just to tune the thing, but we had to ship it.” Kreitzberg himself said that if he had the game to do over again, he would “opt for a smaller world so we could go deeper rather than broader.”

Incidentally, Daglow wasn’t even around when EA finally shipped Amnesia in late 1986. He’d moved over to another company featured in this episode, Brøderbund Software, where he had a brief stint as an executive before starting his own company, Stormfront Studios, in 1988.

While Amnesia was little more than a footnote in EA’s early history, neither Cognetics nor Disch ever developed another computer game. Disch continued writing as an author up until his death in 2008. As for Cognetics, it remained active until the early 2000s as a software design consulting firm. Kreitzberg told Aycock that he decided to “downsize” the company at the turn of the century and he later shifted into academia, taking a position at Princeton University.

One final note: Amnesia recently gained a second life in 2021 in the form of Amnesia Restored, a project led by a team of 32 students at Washington State University Vancouver’s Creative Media & Digital Culture Program to “create an archival version of the game in open web languages.” This Restored version is playable entirely in web browser and restores content from Disch’s original script that had to be cut from the original EA release.

Toy Shop Probably Won More Awards Than Customers

Speaking of Brøderbund, The Toy Shop was a program that garnered strong praise from reviewers like Paul Schindler yet likely was not much more commercially successful than Amnesia. Once again, I acknowledge a lack of sales figures due to the fact Brøderbund was not a public company in 1986. But there are a couple of things that lead me to believe Toy Shop was not that popular with consumers. The first is that by the following Christmas season (1987), retailers had slashed the price of Toy Shop to as low as $17.99, a steep discount from the original $65 price in 1986.

The second indicator was that unlike its more successful sibling, The Print Shop, Brøderbund never released any expansion packs with additional model plans. Print Shop was such a big hit that many of its add-on clip art packs themselves became enormous bestsellers. Even a less well-known product like Brøderbund’s Science Kit, which Stewart Cheifet recommended in the 1985 holiday buyer’s guide episode of Chronicles, managed to crank out a couple of add-on modules. Yet aside from a box of additional card stock and crafting supplies, Toy Shop never saw any new content after its initial release.

The original idea for Toy Shop came from Jimmy Calhoun, who at the time was a Delta Air Lines pilot. According to a February 1987 article by Umberto Tosi for the San Francisco Examiner, Calhoun was a “model-building hobbyist” who had been improvising making his own components using Print Shop. This prompted him to approach Brøderbund with the idea of making a software package specifically targeting model builders. Although Calhoun formed his own company, Active Arts, to developToy Shop, Tosi said that Brøderbund handled all of the programming and testing internally.

Brøderbund chairman and co-founder Gary Carlston told Tosi that there was “some difficulty” in identifying a target market for Toy Shop. Eventually, the company decided it was really an “executive toy” for adults that “lets you show off something made with your computer.” And while Toy Shop may not have broken any sales records, it did win awards. In fact, it was the single biggest winner at the 1987 Software Publishing Association awards, taking home three prizes for Best Creativity Program, Best Concept, and Best New Use of a Computer.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of December 5, 1986.

- Andrew Jong continued to own and run Winner’s Circle Systems in Berkeley until his death in 2017 at the age of 69.

- The PC Type Right was developed by Michael Weiner, who worked at Xerox PARC before spinning off his own company, Microlytics Inc., which was best known for its thesaurus softwareWord Finder. According to a 2002 profile of Weiner by Smriti Jacob for the Rochester Business Journal, Microlytics primarily licensed its spell-checker technology to other companies like Sony and Microsoft. (I don’t think the Type Right made much impact as a consumer product.) In 1990, Weiner sold Microlytics to SelecTronics, the makers of the digital address book that Stewart Cheifet showed George Morrow during the introduction to this episode.

- Venture Business Simulator was definitely a product released at the height of the Reagan administration. The in-game “memos” from company executives all used the names of Reagan cabinet members, such as Treasury Secretary James Baker and Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger.

- 1 Step Software, the publisher of Looking Your Best, was a North Carolina-based software company that was active between 1983 and 1990. From what limited information I could find, aside from offering fashion advice, 1 Step mostly produced golf-related software.

- Edwin Rutsch, the author of The IBM XT Clone Buyer’s Guide, was an unsuccessful candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives from California in 2022.

- IBM did run an ad during the 1987 Super Bowl for the PC Convertible that targeted college students, according to Adland. Apple apparently did not run a Super Bowl commercial that year–and it certainly did not release a PC compatible in 1987.

- There seems to be some confusion over who “invented” the code wheel as a means of software copy protection. Charlie Kreitzberg told John Aycock that Cognetics invented the wheel for Amnesia. But in a game developer forum published in Computer Gaming World–the same issue that featured Scorpia’s review of Amnesia–Robert Woodhead of Sir-Tech Software commented that fellow participant Rod McConnell’s company, Binary Systems, invented the code wheel for their game Starflight. Both Amnesia and Starflight were published by Electronic Arts in 1986. But there was at least one other game, Infocom’s A Mind Forever Voyaging, published in 1985, that featured a code wheel before either of the EA releases. (Special thanks to video game historian Kate Willaert and this 2013 post on the blog Nerdly Pleasures for helping to clarify this issue for me.)