Computer Chronicles Revisited 77 — QuantumLink, Dow Jones Information Services, Delphi, and Minitel

An ad in the October 6, 1985, edition of The Scrantonian announced an upcoming meeting of the Scranton (Pennsylvania) Commodore Users Group on October 8 that would feature a demonstration of QuantumLink, a “new computer information network.” The people who attended that meeting could not have known this, but they were likely among the very first members of the general public to see what a few years later would morph into America Online, one of the dominant online services of the 1990s.

Steve Case, the man who would become America Online’s CEO and go on to lead the company into one of the most disastrous deals in U.S. business history–AOL’s 2001 merger with Time Warner–was a guest in this next Computer Chronicles episode, the first to be broadcast in 1987. At this point, Case was merely QuantumLink’s head of marketing. His service had yet to escape the confines of the Commodore 64. Indeed, QuantumLink was just one of many companies featured in this first of a two-part look at “on-line services.”

Stewart Cheifet opened the program by demonstrating one of QuantumLink’s features to co-host George Morrow–a casino. There was a slot machine on the screen with fully animated graphics and a chat window to talk to other users. (Cheifet emphasized that no real money was involved.) Cheifet asked Morrow what something like the “casino” told him about this approach to online information. Morrow said the game worked well from a medium that was “warm” to “sometimes hot.” Some of the other online services made you think that you were back in the era of talking to a teletype rather than a computer. You had to play your interface to the warmth of the media, and some of the better online services were doing that–and eventually they would all have to do so.

Another Chronicle Goes Online

Wendy Woods presented her first report focusing on the San Francisco Chronicle, which was now available online. Woods said that newspaper publishing was largely an art of “mind over matter”–how to put ideas and events into physical shape as quickly as possible. One of the obstacles to assembling that information has been the printed document itself, i.e., the thousands of pages that flowed out of printing presses every day.

Typically, Woods said, the masses of photos, drawings, and words were carefully clipped and stored in bulging files, where they became historical material. But today, at some major newspapers like the Chronicle, paper files were being replaced with online digital storage. Working through an online service called DataTimes, the Chronicle was building an electronic library. Each day’s news stories were added to the database within 24 hours.

Woods said the key to the system’s speed was the software, which took the final story as entered into the newsroom’s computers and automatically re-formatted the writer’s editing commands into retrievable library form. After some classifying and editing by the Chronicle’s library staff, stories could be recalled by keywords, subject, or other cross-references. If a reporter needed background information, they could scan through the titles of past stories and view the full text of those that were the most relevant.

DataTimes gathered articles from 30 metropolitan newspapers, Woods said, as well as some foreign news services. In the early days of computing, memory storage was precious and costly. But today, the newest form of information storage was taking its place alongside one of the oldest and most valued.

QuantumLink Hoped Graphics Would Make the Difference

Steve Case and Stephen Fickes joined Cheifet and Morrow for the first studio round table. As previously mentioned, Case was vice president of marketing with Quantum Computer Services, which operated QuantumLink. Frickes was an account executive with CompuServe.

Morrow opened by noting that CompuServe was owned by the tax preparation firm H&R block. (Morrow made this sound like a recent investment, although it took place back in 1980.) He asked Fickes what CompuServe brought to H&R Block. Fickes said that there were three different areas where H&R Block benefited. The first was access to online information. The second was network services, i.e., linking personal computers to host computers run by large corporations. Finally, there was the building of a company’s information service that people could remotely access. All three of these areas were growing very quickly.

Cheifet noted that he loved online services, but there were also a lot of complaints from users. What were the biggest complaints that Fickes had heard? What would people like to see done better? Fickes said the main complaint was about time lag when jumping from one service to another within CompuServe. Cheifet said his main complaint was the use of different commands in different parts of the service. Why couldn’t that be cleaned up so you only needed to learn one set of commands? Fickes said that tended to be a function of how many different bits of information there were on the service.

Morrow interjected, noting that online services had a lot in common with traditional databases and spreadsheets. So why not get together with a company like Ashton-Tate (which made dBASE) or Lotus to develop a more familiar user interface? He added that Lotus was teaming up with one of the services, although he didn’t say which one. Fickes said that CompuServe was exploring all those areas.

Cheifet turned to Case and asked him about the feedback he’d received on QuantumLink, which had a more graphical-friendly interface. Case noted that QuantumLink had only launched about a year ago and when they entered the market they saw three problems for consumer users of online service. The first was that they were too expensive. The second was that they were just too difficult to use. And the third was that they weren’t fun. So QuantumLink’s goal was to develop a service specifically for Commodore users that was very easy to use. Echoing Cheifet’s earlier point, Case emphasized the commands were uniform throughout the entire QuantumLinnk system. The service was inexpensive, useful, and fun.

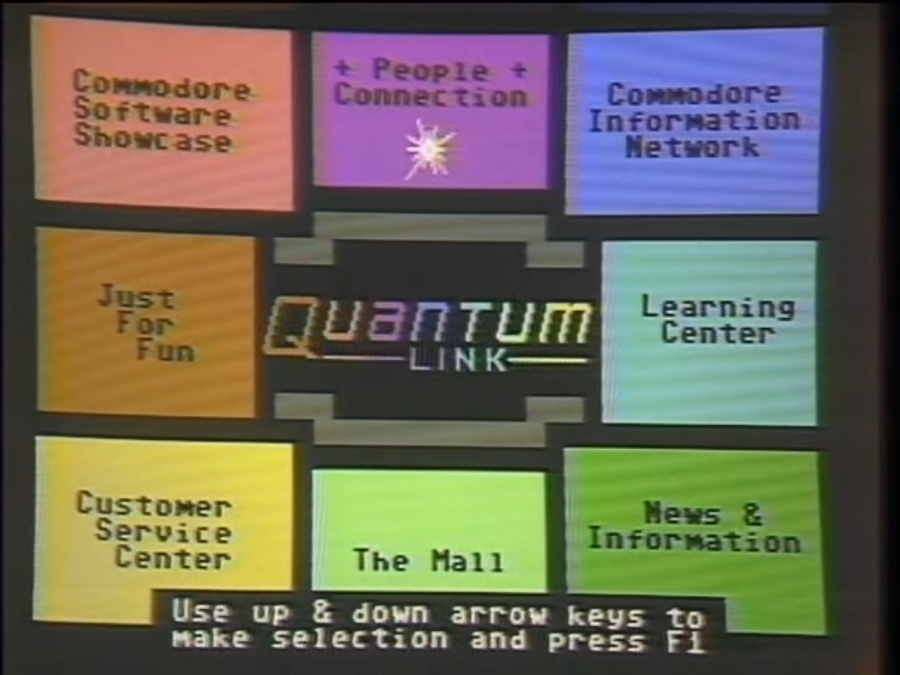

Cheifet asked Case for a demonstration of QuantumLink. Case showed the service’s main menu (see below). He explained there were eight different departments on the service. You used the cursor keys on the Commodore keyboard to move around the options. Cheifet asked about the “People Connection” department. This actually loaded a screen from disk, Case explained, so that the graphics didn’t have to be transmitted over the network.

“People Connection” was what Case called the “social center” of the system. Users could meet in rooms like a “lobby,” chat with each other, and conduct conferences with special guests such as rock stars and computer programmers. With respect to the user interface, you only had to press one key to pull up a list of commands, and again that was the same across the entire service.

Case then briefly explained how online chat worked, i.e., you typed a message and sent it to everyone who is in a particular room. He added that users could create their own rooms for specific topics like discussing Computer Chronicles. Cheifet asked if anyone ever said anything meaningful or useful in these chat rooms? Case reiterated that they hosted a number of specific conferences with a dedicated schedule. QuantumLink even published a program guide much like a TV Guide. There were typically 7 or 8 such events each night. But overall, the rooms were a place to meet friends and talk about their interests.

Cheifet said that he’d heard stories that QuantumLink would go beyond Commodore sometime. Was that true? Case said they were looking at it. Right now they were focused heavily on the Commodore market, but he thought QuantumLink’s approach would work in other segments of the home computer market as well.

Turning back to Fickes, Cheifet asked if CompusServe was playing around with ideas like what QuantumLink had done with respect to the user interface. Fickes said they were playing around with graphics approaches. But given that CompuServe ran on many different types of computers, they were somewhat limited on what they could do locally. But he said that CompuServe was coming out with a new product oriented for IBM PC users, which would be more effective in accessing services within that environment.

A Day in the Life of a Sysop

Wendy Woods presented her second remote segment, which profiled Don Watkins, a CompuServe systems operator (sysop). Watkins lived in an unincorporated area of Sonoma County, which as Woods noted was far from a “bustling technological center.” But from this location, which appeared to be a farm, Woods said that over 25,000 CompuServe users could receive answers to technical questions about their IBMs and compatible PCs.

Woods said this farm was Watkins’ home and office. Watkins, formerly an information systems manager in the banking industry, was now a sysop for the five IBM special interest–or SIG–areas on CompuServe. (Those areas were New Users, Communications, Hardware, Juniors, and Software.) Watkins supervised conference areas, data libraries, and message bases of CompuServe’s Ohio-based mainframes.

Watkins told Woods that users could get free or low-cost programs, user-supported programs, and they could also access a huge intellectual base of talent and experience of people who had tried and reviewed other products.

Woods said that Watkins had managed the IBM forums on CompuServe for five years. In that time, he’d watched the members change from hackers and hobbyists to mainstream computer users who were just interested in getting a job done. The SIGs had taken on a much broader appeal, and in our information-driven society, such resources could only get more popular. For example, Watkins said that he could talk to someone in New York City or Miami or Dallas about a product that they might know more about than him. And having such a two-way dialogue was quite valuable.

Delphi Promised Cheaper Online Access

Clay Cocalis and Nancy Tully joined Cheifet and Morrow for the next segment. Cocalis was a sales representative with Dow Jones & Company. Tully was senior director for information services at Delphi.

Morrow opened by noting that Dow Jones had long been a leader in financial services. He asked Cocalis if Dow Jones might not exert similar leadership in bringing standards to communications software and online services. Cocalis replied that was a very challenging question. It was not easy to get together with the other companies. Morrow retorted that Dow Jones was big and prestigious enough to press forward and get a standard done. Cocalis said the problem was that there were so many different kinds of computers, Dow Jones would be getting itself into a “nightmare” trying to support each type of equipment (Apple, IBM, etc.), and you would have to make sure the products worked on every machine.

Cheifet asked Cocalis what kind of people subscribed to Dow Jones online service. Cocalis said there were a large number of subscribers. But their best market was their corporate customers, e.g., Fortune 500/1000 companies. Cheifet asked Tully the same question about Delphi. Tully said Delphi’s largest growth over the past 18 months had been with the home user. The typical user was someone who had bought a new computer. Delphi was also focused on growth in the small business market.

Morrow asked Tully what Delphi had done to make its user interface better for users. Were they focused on a specific hardware or software package? Tully said no, Delphi cooperated with a lot of the software manufacturers in getting Delphi into their products. But Delphi didn’t have its own dedicated software package. She added that Delphi had been judged “easy to use” by a number of product reviewers.

Cheifet asked Cocalis for a demonstration of the Dow Jones service. Cocalis showed a database that contained the last 90 days of news on any publicly traded company, which could be searched by stock or industry symbol. The information was as recent as 90 seconds and updated throughout the business day. For example, he pulled up the last 90 days worth of headlines for IBM. There were nine pages of headlines and a two-letter code next to each headline. The user could retrieve the full text of an article by entering the corresponding two-letter code.

Morrow asked if you could use the service to follow 2 or 3 specific companies. Cocalis said absolutely, there was a tracking service that allowed the user to create up to 5 “profiles” with 25 stocks each. This would let you get the latest stock price and the past two days worth of news.

Morrow clarified that Dow Jones’ interface was standard across all of its services. Cocalis said that was correct. He then continued his demo by pulling up a listing of headlines on the computer industry as a whole. There were 20 pages of headlines. Cheifet asked Cocalis what command he used to do that. Cocalis said he typed i/edp. The “i” stood for “industry,” while “edp” stood for “electronic data processing.” Dow Jones categorized every major industry to make it easier for the user to find a specific industry. Cheifet asked if all the codes were listed in a manual. Cocalis said there was a manual as well as a separate online database. Morrow asked how you accessed that database. Cocalis said there was a specific command for “database.”

Cheifet next asked Tully how Delphi was different from the other online services profiled so far. Tully said Delphi was a relatively new service and it differed in that it originated as an online service as opposed to being a byproduct of excess computer capacity. Tully pulled up Delphi’s main menu. She noted the system’s many features, including electronic mail and real-time conferencing.

Morrow asked how many subscribers Delphi had. Tully said that was proprietary information. But she said the subscriber base had been growing at a rate of between 12 and 15 percent a year. Tully then continued her demo. She selected “Groups and Clubs” from the main menu, which she said had been the most popular part of the service over the past 18 months. (Cheifet noted this was basically the equivalent of CompuServe’s SIGs.) She selected the Macintosh group by typing mac. A welcome message followed listing the manager and sysop for the group, a conference schedule, and new forum messages. Morrow noted the system beeped when she entered the group. Tully said that was an indicator that she had new messages in response to one of her earlier posts. She had posted a question about Microsoft Excel and another user (MADMACS) had posted an answer.

Cheifet asked if Delphi was less expensive than some of the other online services. Tully said a lifetime membership was only $49.95. Connection time ranged from 11 cents per minute at night to 29 cents per minute at night from anywhere in the United States. There were no monthly minimums or extra charges for faster (1200 baud) modems.

Was France’s Approach to Online Services “Socialist Hap”?

Jack O’Grady joined Cheifet and Morrow for the final segment. O’Grady was the U.S. representative for Intelmatique, a subsidiary of France Telecom. O’Grady demonstrated the Minitel, a small computer terminal used to access an online service run by France Telecom.

Cheifet said the Minitel in the studio was already connected to Paris. He asked O’Grady to show how you could shop for a car using the system’s classified service. O’Grady pulled up a menu listing 39 different car brands. He said you could compare different makes and models. He selected a Mercedes 420 SE and a Jaguar Sovereign 3.6. This brought up a graphic display comparing the features of the two cars.

Morrow noted the French government gave the Minitel terminals away for free. Wasn’t that just a lot of “socialist hap”? O’Grady said the terminals were actually loaned, in the same manner as AT&T leased telephone handsets. Morrow pressed, Why should people get a terminal for free? O’Grady said it cut down on the paper telephone directories, as anyone who accepted a Minitel had to forgo receiving a traditional phone book. It would also eventually lead to reductions in the number of telephone operators needed to provide information.

How long would it take before the Minitel paid off over paper directories, Morrow asked. O’Grady said France Telecom believed it had already paid off. The original estimates were that it would take five years to pay off, and it had only taken four-and-a-half years.

O’Grady demonstrated another part of the Minitel service, which offered the newspaper Le Monde online. This service was updated every two hours. Cheifet asked if people were actually reading the full paper online. O’Grady said absolutely, and that included the full paper, with sections like classified ads and even horoscopes. Morrow asked about financial information. O’Grady said you could search for information from the Bourse stock exchange. Despite his earlier “socialism” remark, Morrow seemed impressed by the system. Cheifet added the Minitel approach really helped to standardize the service.

Winter CES Brought Promises of Laser Printers, 3D Glasses for the Atari ST

Stewart Cheifet delivered this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in January 1987.

- Atari was reportedly coming out with a low-cost laser printer during the first quarter of 1987. Cheifet said the rumored $1,500 printer would be similar to the Apple LaserWriter but without an on-board processor or memory. Atari was also expected to bundle this new printer with a $3,000 desktop publishing package that would include a 1040ST with a hard disk.

- At the winter Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, ANTIC Software showed off its new Stereotek glasses, which could turn an Atari ST monitor into a 3D display using liquid-crystal shutters that opened and closed in sync with the monitor’s refresh rate. (The 3D effect was similar to a View-Master.) Cheifet said there was already a software package called CAD 3-D that could be used with the glasses.

- The annual Macintosh expo was held in San Francisco. Cheifet said there was a 40 percent increase in exhibitors.

- US Robotics announced a new deal on its 9600-baud modems for BBS operators; they could receive the modem at half-price (around $500) if they posted a notice on their board advertising the product. Cheifet noted that a similar deal two years ago helped push sales of US Robotics’ 2400-baud modems.

- Paul Schindler reviewed The Page (Orion Microsystems, $22), a DOS utility program.

- A recent study by the federal government concluded that the government was way behind private industry in upgrading computer equipment. Cheifet said the study found that the typical Fortune 500 company kept a computer for less than 5 years, while the typical government office kept a computer for more than 10 years.

- Engineers in Scotland reported a major development in producing “laser” computer chips that used light waves rather than electronics thanks to a layer of coated glass that could either reflect a light beam or allow it to pass through. Cheifet said this could be the key to fast, compact parallel computing.

- Atari founder Nolan Bushnell was now marketing “Techforce” toys. These were robot toys that could be activated by inaudible signals in a television program. This allowed the toys to become interactive participants with the TV show. Cheifet said that the Techforce robots were due out by fall 1987 and “may well become the high-tech toy hit of the next Christmas shopping season.”

The Face That Launched a Billion Floppy Disks

The story of QuantumLink actually began with another online service that has been frequently mentioned on Computer Chronicles, The Source. As I discussed in a prior post focusing on The Source, that service was founded by William von Meister in 1979, who lost control of the project in a fight with his business partner. Undaunted, von Meister quickly moved onto his next idea–selling music online.

Now, we’re not exactly talking about the iTunes store here. Rather, von Meister’s proposed “Home Music Store” involved beaming music via satellite to local cable television systems, who in turn would send a digital signal into subscribers’ homes, and then those subscribers could then tape record the songs on their own stereos.

Von Meister spent much of 1981 peddling this idea to investors. But it quickly collapsed when Warner Brothers backed out of a deal to license its music catalog to the Home Music Store. A Warner Brothers executive, however, suggested von Meister try his idea out with another technology: video games. Of course, in 1981 Warner Brothers also owned Atari, Inc., then the leader in the home video game console market.

According to Alec Klein’s 2003 book, Stealing Time: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Collapse of AOL Time Warner, von Meister eagerly embraced this new concept. He “developed a cheap and fast modem–basically, a little box with a lot of electronics stuffed in it.” This modem would plug into the Atari 2600 console like a cartridge. With the modem connected to a telephone line, the user could then download games remotely.

Klein said von Meister managed to raise $400,000 in initial funding. He then formally incorporated the business in Virginia as the Control Video Corporation. In January 1983, von Meister held the first public event for his new project at the Tropicana Hotel in Las Vegas. This was during the winter Consumer Electronics Show, but von Meister didn’t want to pay for an actual booth. Instead, he hired a group of showgirls to lure potential customers to his suite at the Tropicana. According to Klein, von Meister took 150,000 orders.

It was at this point that Steve Case entered the story. Born in 1958, Stephen McConnell Case graduated from college in 1980. He then managed to convince Procter & Gamble to hire him as an assistant brand manager, where he oversaw a hair-conditioning towelette. That job didn’t last long, however, and Case later ended up doing market research for Pizza Hut, “traveling to small pizza shops [and] testing pizza flavors,” as Klein put it.

So Steve Case was not what you would call a success. But it turned out that his older brother Dan was, having made his fortune in investment banking and, more importantly, contributing several million dollars in capital to von Meister’s new online video game venture. You can probably guess what happened next: Steve Case came to see von Meister’s Tropicana “show” in Las Vegas and Dan Case “convinced” von Meister to give his younger brother a job as a part-time marketing consultant at Control Video Corporation.

Although Control Video’s new product–dubbed the GameLine–was ostensibly about video games, even in early 1983 von Meister saw it as a means of building a more comprehensive online service. The first ads for GameLine, which started appearing in newspapers in September 1983 (see below), made it explicit that “video games are only the beginning,” and promised additional services that Control Video planned to offer, including electronic mail, stock information, and sports scores. Von Meister told the press that same month that about 3,000 subscribers had already purchased the GameLine “master module,” which included the modem hardware.

To be clear, customers were actually renting games rather than buying them. A customer purchased the hardware, dubbed the “Master Module,” for about $50. They then had to call GameLine to register for the service, which involved a separate fee, and provide their credit card information. Once registered, the user could download games for $1 each, but they could only play it 10 times. Control Video spun this as being able to try a game out before you bought it at the store.

The initial GameLine catalog boasted several dozen games. But they were all from third-party publishers. The two biggest publishers on the Atari 2600 platform–Acitivision and Atari itself–did not participate in GameLine. In December 1983, Atari and Activision announced their own joint venture to produce a similar technology, but I don’t think it ever came to fruition.

Indeed, Control Video’s timing for GameLine could not have been worse. By late 1983 the home video game market was in the midst of a full-scale collapse, largely brought about by the excessive amount of Atari 2600 games in retail distribution. In December 1983 you could probably just buy one or more games for $1 at a store desperate to clear inventory. And retailers probably weren’t eager to keep a product on shelves that might only further cut into those sales. Ultimately, Klein said that while Control Video shipped 40,000 Master Modules to retailers, 37,000 of them came back and were thrown in a dumpster behind the Control Video offices.

Altogether, Control Video spent $20 million on GameLine and only managed $40,000 in revenue–and $15,000 of that figure came from selling rides on a hot air balloon that von Meister bought for the launch event at the Tropicana. One of von Meister’s infuriated investors decided to bring in an old Army buddy, Jim Kimsey, to serve as a “consultant” to von Meister. Kimsey had no background in technology, but he owned a number of successful bars and restaurants in the Washington, DC, area near Control Video’s Virginia headquarters.

Kimsey only intended to stay a short time before returning to his own businesses. But an early 1984 meeting in Palo Alto, California, with investors and the board of directors quickly turned into a coup, ousting von Meister as CEO and replacing him with Kimsey, who brought in Marc Seriff, an engineer with a decade of experience in telecommunications, to run the technical side of the business.

Kimsey also promoted marketing consultant Case to vice president of marketing in 1985. According to Klein, this was less about Case’s raw talent or accomplishments than the fact that he was young and cheap (and Kimsey had fired everyone else above Case on the organizational chart). Kimsey also knew that keeping the younger Case around would help convince his brother to keep pouring money into the struggling company.

This was also the period when Control Video renamed itself Quantum Computer Corporation. The name change became official in May 1985. By this point the company was down to just 10 employees, including Case. GameLine was long dead and Kimsey’s initial plan was to quickly sell what was left of the company. He approached Apple, but Klein said the executives there “practically rolled on the floor” with laughter at the suggestion.

Kimsey found a more willing partner, however, in Commodore International. Commodore didn’t buy Quantum but rather agreed to provide “extensive marketing support” for a new online service that Quantum would run. This was announced in July 1985. From Commodore’s perspective, they saw it as a way to extend the life of its flagship Commodore 64 home computer.

As part of this new arrangement, Commodore introduced Kimsey and his team to PlayNet, a small software company based in upstate New York. Founded in 1982 by former General Electric engineers Howard Goldberg and David Panzi, PlayNet was another early online service that stressed games and social activities as opposed to business uses. Kimsey licensed PlayNet’s software for $50,000 to use with his company’s news Commodore online service, which was named QuantumLink.

QuantumLink formally launched in November 1985. Early adoption was slow. Despite a huge marketing push from Commodore and millions of C64 machines in households, there were only 10,000 QuantumLink subscribers by January 1986. It was still promising enough to help Kimsey attract additional investors for the company, and by the time this Chronicles episode taped in December 1986, QuantumLink had around 50,000 subscribers.

As QuantumLink rose, so did Case. Kimsey promoted Case to executive vice president in 1987, effectively designating him as the heir apparent. Case’s rise to the top was almost derailed, however, by of all things Apple. In May 1988, Apple announced its own online service for Macintosh users called ConsumerLink–later dubbed AppleLink Personal Edition–which Quantum Computer Services would run. But the deal ran into trouble. According to Alec Klein, “Apple had been difficult to deal with from the beginning, demanding that Quantum adhere strictly to Apple’s look and feel in the design of [AppleLink Personal Edition].” Apple was also refusing to pay the millions of dollars it owed to Quantum for its work. Klein said that Quantum board members wanted to fire Case, as he’d been in charge of the deal, but Kimsey saved his protege’s job.

Quantum ended up bringing the AppleLink Personal Edition to market on its own without Apple’s support. In late 1988, Quantum and Tandy Corporation also launched PC-Link, a QuantumLink-type service focused on Tandy’s line of IBM PC compatibles. By early 1989, Quantum was also working on a user interface for “California Online,” a proposed online service that would have been run by Pacific Bell.

When Pacific Bell decided to abandon California Online in October 1989, Case took some of the concepts developed for that project and merged it into AppleLink Personal Edition, which was relaunched as America Online on October 2, 1989. (Klein said Case came up with the AOL name himself.)

I won’t delve deeply into the rest of AOL’s history at this time. In brief, Case became president and CEO of the company in 1991, the same year it was officially renamed from Quantum Computer Services to America Online Inc. Kimsey, who remained chairman of the board, briefly reclaimed the CEO’s title to reassure investors when America Online went public in March 1992. After the initial offering raised $66 million, Case was reinstated as CEO. Case also became chairman upon Kimsey’s retirement in 1995. In 2001, Case led America Online into the infamous merger with Time Warner. Case became executive chairman of the combined company but resigned in 2003, the same year that Klein published his book. Case left the AOL Time Warner board altogether in 2005 and started the venture capital firm Revolution LLC, which he still runs today.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of January 8, 1987.

- Stephen Frickes remained with CompuServe until 1998, rising to become director of international sales. He later held sales director positions with UUNET, MCI Corporation, and Verizon. His most recent position was as senior director of business development with Flex, a multinational manufacturing company.

- Don Watkins also remained with CompuServe until the mid-1990s, moving over to the Microsoft Network (MSN) in 1997, just a week after Steve Case’s America Online purchased CompuServe from H&R Block.

- Clay Cocalis is currently the chief revenue officer at Exterro, a legal software platform company. After leaving Dow Jones in 1999 he served as a senior executive with a number of companies, including Tower Group, Epiq, and Morae Global. He joined Exterro in August 2021.

- The DataTimes service featured in Wendy Woods’ first report originated in Oklahoma. Datatek Corporation was founded in October 1981. It originally sold an internal database to The Oklahoman and Times newspaper for use by its editors and reporters. A public version of the database–DataTimes–went online in May 1983. In December 1983, the parent company of The Oklahoman and Times acquired Datatek as a subsidiary, which was renamed DataTimes Corporation, and started signing up other newspapers like the San Francisco Chronicle. Bell & Howell acquired DataTimes Corporation in August 1996.

- Delphi’s origins can be traced back to the Northeast Computer Show held in Boston in October 1981. One of the exhibitors was “The Kussmaul Encyclopedia,” which was actually an Apple II or TRS-80 computer bundled with a 300-baud modem that could be used to dial an online database containing the actual encyclopedia. Wes Kussmaul, the man behind the encyclopedia, quickly decided to drop the hardware and software bundle and instead focus on building the online database. The company he founded, General Videotex Corporation, launched the Delphi online service in March 1983. Delphi never grew to the same degree as AOL or CompuServe, however, with around 100,000 subscribers at its peak. In September 1993, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation purchased General Videotex for $15 million and renamed the company Delphi Internet Services. But two years later, Delphi was down to around 50,000 subscribers and in 1996, New Corporation sold Delphi to a group led by the company’s former CEO, Dan Bruns, for “relatively little cash,” according to Fortune. Bruns decided to reinvent Delphi as Delphi Forums, an advertising-supported web portal. Delphi Forums subsequently went through several more ownership changes before Bruns reacquired the company in 2011. Delphi Forums remains in business today.

- The Minitel enjoyed a long run in France, rolling out nationwide in 1982 and continuing to run until 2012. According to Forbes, by 1997 there were 6.1 million Minitel units in France and an additional 600,000 users accessing the service through PC emulation software. But a 1989 joint venture between France Telecom and US West to market the system in the United States ended after just four years. Forbes noted that unlike the French government, US West wasn’t prepared to subsidize the cost of providing terminals, so American users were expected to pay $15 per month for both the terminals and the service. And by the late 1980s, the Minitel was considered obsolete compared to PCs. Intelmatique continued marketing Minitel in the United States well into the late 1990s, but Forbes said there were never more than a few thousand subscribers.

- Atari Corporation did eventually release that laser printer. Known as the SLM804, it made its first public appearance an Atari trade show in London in April 1987, although the demo unit didn’t work, according to NewsBytes. Contemporary news sources reported that the printers didn’t start shipping until sometime in the spring of 1988, by which time the price was $2,000, or $500 higher than Stewart Cheifet’s initial report suggested.

- Nolan Bushnell’s “TechForce” robots proved to be a dud. Wendy Woods first reported on the project for NewsBytes, where she said Bushnell had obtained approval from the FCC for local television stations to transmit an “inaudible broadcast signal” to the toy robots during the airing of an accompanying “TechForce” cartoon. DIC Entertainment–probably best known in the United States at that time for producing Inspector Gadget–was commissioned to produce the cartoon. The project almost immediately faced public opposition. In February 1987, a group called Action for Children’s Television filed a protest with the FCC, arguing that Bushnell’s scheme went too far in blurring the line between programming and advertising, and would create a “second class of viewers” whose parents could not afford the $250 toys. Bushnell dismissed the concerns, but in August 1987, the television show was abandoned because, according to NewsBytes, there were “almost no television stations lined up to take it.” (DIC also said there was a “dispute over money and contracts.”) Bushnell’s company, Axlon, Inc., still apparently sold the robots–without the cartoon-enhanced features–but ended up writing off a $325,000 loss on the whole endeavor.