Computer Chronicles Revisited 107 — KoalaPainter, the Wine Steward, Skate or Die, Master Composer, and Keyboard Controlled Sequencer

At the June 1983 Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, Commodore International announced a cut in the wholesale price of its Commodore 64 (C64) computer from $360 to $199. This move was the latest salvo in a price war initiated the previous August by Commodore’s arch-nemesis, Texas Instruments, which announced a $100 rebate on its TI-99/4A computer, bringing its effective price down to $199. This had been TI’s attempt to undercut Commodore’s VIC-20, the predecessor to the C64, which was then priced at $239. But now that Commodore had brought the price of the newer and more capable C64 down to $199, TI was boned.

Indeed, longtime Commodore president Jack Tramiel wasn’t messing around. He also slashed the prices of Commodore’s peripherals and software by as much as 50 percent. This spurred record consumer demand for the C64 and C64 accessories. So while Texas Instruments reported a $119.2 million loss for its second quarter of 1983 and exited the entry-level computer market soon thereafter, Commodore posted record numbers. For the company’s fiscal year ending June 30, 1984, Commodore International reported net income (profit) of $143.8 million.

Sadly, this would be the high-water mark for both Commodore as a company and Tramiel as a CEO. In January 1984, Tramiel suddenly resigned as Commodore’s president, the culmination of a strained relationship with the company’s longtime chairman and controlling shareholder, Irving Gould. A few months later, Tramiel took over the home computer and video game console assets of Atari, Inc., a company that had an even worse 1983 than Texas Instruments. Tramiel’s new Atari Corporation would then battle Commodore at the lower end of the 16-bit personal computer market for the rest of the 1980s, with both companies fading into irrelevance as the larger market embraced and extended the IBM PC compatible standard.

But throughout the late 1980s, the C64 continued to thrive, at least with consumers who were happy to keep buying millions of the cheap computers every year. In fact, when Computer Chronicles finally dedicated an episode to the C64 in March 1988, the machine had been on the market for nearly six years–an eternity for any computer–and it was still just halfway through its production life, which didn’t come to an end until Commodore filed for bankruptcy in 1994.

Stewart Cheifet opened the episode by showing Gary Kildall a new game recently released for the C64 called Tetris. Cheifet noted it was the first software program written by a Russian author to be published in the United States. But Cheifet was more interested in the fact the program’s U.S. publisher, Spectrum Holobyte, decided to release Tetris first on the C64, the “Model T of personal computers.” How come people were still buying these machines and writing software for it?

Kildall, briefly recapping the price wars, said that when Jack Tramiel ran Commodore, his philosophy was to minimize the end-user price and flood the market with product. Tramiel did it with a $10 calculator in the mid-1970s. (This was an earlier price war that also involved Texas Instruments.) And he did it by selling the C64 at under $200 when the competition was charging five times the price for their machines. Ultimately, Kildall said the C64 was just a good basic computer for a very affordable price. There were roughly seven million C64s in the United States alone, which provided a good bed for software developers who could amortize their costs across all of those units. So you also ended up with a lot of good software at an affordable price.

Berkeley Softworks Pushed the C64’s Limits with GEOS

Wendy Woods’ first remote segment featured Berkeley Softworks, the developers of GEOS, a graphical operating system for the Commodore 64. Woods said the history of personal computers was marked by some spectacular successes and failures. But the award for popularity had to go to the C64, the little 8-bit machine that refused to die. The C64’s commercial success and its enormous user base inspired developers like Berkeley Softworks, a company located next to the University of California, Berkeley.

Brian Dougherty, Berkeley Softworks’ CEO, told Woods that they looked at the existing markets–first the Commodore 64 and then the Apple II–and realized that it took awhile for people to really push a machine to its total limits. And it was only now starting to catch on that the key to pushing those limits was using sophisticated development tools. With such tools, Berkeley developed applications for these machines that people didn’t think were possible.

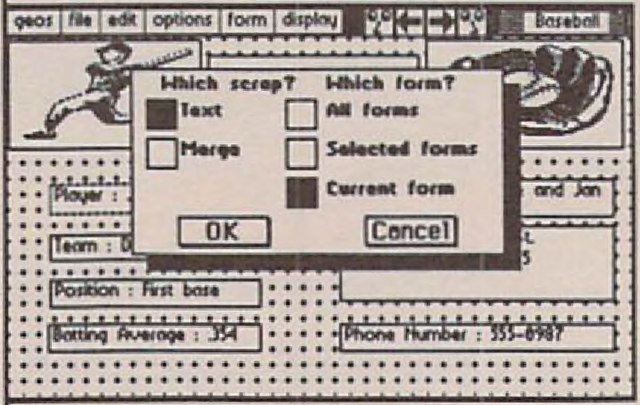

Woods said that GEOS was Berkeley’s most important product. GEOS provided a graphic interface for the C64 and Commodore 128, featuring pull-down menus, icons, and windows. As Doughtery alluded to, this new operating system opened the door to some very sophisticated applications, such as a spreadsheet called GeoCalc and GeoFile (see below), a database with user-designed forms. There was even a desktop publishing package, something that usually required a lot of memory and a big budget. But with Berkeley Softworks, it was all in the code.

Dougherty elaborated that it came down to coding much more efficiently. The theorem of computer science was that any computer program could be implemented by a one-bit Turing machine. So even the C64’s 8-bit processor could do all of the things that a much more expensive computer such as a Macintosh or an IBM PC were capable of doing. Now, the C64 might not be able to do it as fast, but Berkeley tried to make up for the limitations by programming more efficiently. But Dougherty reiterated that you could technically do anything with the C64.

Knitting with Power on the C64

The bulk of this episode largely focused on actual Commodore 64 users rather than software developers. For this first studio segment, Mike Dunsmore and Lucy Morton joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Dunsmore was a member of the Commodore Users of the Peninsula (CO-OP). Morton belonged to the Diablo Valley Commodore Users Group.

Kildall opened by asking Dusnmore about the composition of user groups like CO-OP. Were they principally C64 users? Dusnmore said some user groups were just for C64 users. Some had both Amiga and C64 users. Kildall noted that these user groups commonly communicated over modems. Dunsmore said yes, there were two or three bulletin board systems (BBSes) used by his group. Kildall asked if the BBSes actually ran on C64s. Dunsmore said they usually ran on another machine, but there might be a C64 database.

Turning to Morton–who looked like she could be Dunsmore’s grandmother–Kildall said he might be presumptuous, but she didn’t look like the average game player using a C64. Why did she buy a C64? Morton said she had always been interested in computers. Her husband also did some programming, and it was very easy to program in BASIC on the C64, particularly since you could readily correct mistakes.

Kildall asked Morton to demonstrate a program she wrote on the C64 to help her make sweaters. Morton clarified it helped her to chart them; making them was something else. She explained that her program was interactive. Before you began, you had to know the number of stitches per inch and rows per inch that you wanted, which you obtained from a swatch of cloth. For her demo, Morton instructed the computer that she wanted to make a jacket with a knit-on band and a V-neck. Essentially, you answered a series of questions regarding all of these details. The program then produced a series of written instructions that the user could print out.

Cheifet returned to Dunsmore and asked him to explain how he used the C64 to make artwork. Specifically, Dunsmore created demo scenes, some of which he used as title screens for other programs. Cheifet asked about the tools he used in addition to the C64. Dunsmore said he used KoalaPad, a graphics tablet, and its included KoalaPainter software.

Dunsmore then provided a brief demo of KoalaPainter. He pulled up a sample image that he created for a BBS called “Wacko World.” Then he showed a menu that he designed for another program. Cheifet asked about adding artwork to the screen. Dunsmore showed how you could edit individual pixels in the image. Kildall noted that this was a composite video signal, the same as used by camcorders and similar devices. So you could use KoalaPainter to make titles and similar graphics for home videos. Cheifet pointed out that Dunsmore effectively had a complete graphics design station that probably cost him less than $400.

User Groups Supported C64 Neophytes

Wendy Woods’ second and final remote segment visited a Commodore users group meeting in Foster City, California. Woods said when you bought for price, you didn’t always get good service. That was especially true for Commodore 64 and 128 owners, whose low-cost machines received no support from the mass merchandise retailers that sold them. User groups like the one in Foster City allowed these computer owners to try out programs, trade tips, and just get the help they needed.

Ralph Hornbrook, a member of the Foster City group, told Woods that it was almost impossible to describe the help that someone like him–an “absolute neophyte” just 3 or 4 years ago–received. He started out knowing nothing about how computers worked. He knew he wanted to get into computer, but he didn’t know how.

Sam Gold, the organizer of the group, said they offered an informal hand-holding type meeting so that if someone didn’t understand how to use a computer, the other members would sit down with them, show them how to operate it, and how to do the various processes required to run programs. Basically, the group showed new users how to put everything together and use their computer to productive advantage.

Woods said that despite the fact the more powerful Amiga was now seen at Commodore user group meetings, interest in the C64 was still going strong. The price kept dropping and people kept buying them–which was why it should come as no surprise that membership in groups like the one in Foster City had actually increased over the years.

A Machine for Skateboarding and Wine Enthusiasts

Malcolm Lowe and Kelly Flock joined Cheifet and Kildall for the next segment. Lowe was a consultant and programmer as well as a member of the Commodore West users group. Flock was a product manager with Electronic Arts, one of the leading commercial publishers of C64 software.

Kildall asked Flock about the current importance of the C64 to EA’s marketing relative to other platforms such as the Apple II and the IBM PC. Flock said the Commodore was very improtant. In fact, it was EA’s second most-important platform behind the IBM PC and compatibles. Kildall asked what made the C64 a good target for games. Flock said it was the leading home computer with an installed base of about 7 million units. And since it was a game-intensive system, it was a natural place for EA to be.

Turning to Lowe, Kildall asked about his program, The Wine Steward, which was running on a C64 in the studio. Lowe said the program was designed to help people who were unfamiliar with purchasing wine to make a choice based on what they were going to have for dinner. Cheifet noted this program was actually used in supermarkets. Lowe said that was correct.

Lowe then demonstrated Wine Steward. He used the C64’s joystick to navigate the menus, but he explained that in a supermarket display the machine was in an arcade-style cabinet with buttons. (The software displayed the name of Lucky’s, a California-based supermarket chain.) The user first selected the type of food they were having–American, “International”, Dessert, et cetera–and then selected a more specific dish from a sub-menu. For his demo, Lowe selected “Deli and Picnic” food, and then “Cheese” from the sub-menu.

The program then showed three separate screens offering a choice of nine different wines to pair with cheese. The first screen showed three “budget wines” priced between $2.49 and $5.99. The second screen offered three “popular priced wines” ranging from $3.99 to $4.99. The third and final screen displayed “premium priced wines” priced between $6.99 and $18.98.

Kildall asked how customers liked this program. Lowe said they seemed to take to it quite well. Cheifet asked if there was any particular reason Lowe wrote Wine Steward for the C64. Lowe said it was an easy computer to program for. It had a lot of features, particularly color, and you could program different fonts for it.

Turning back to Flock, Cheifet asked him to demonstrate EA’s latest C64 game, Skate or Die. Flock said it was a “multi-event” game that functioned as a skateboard simulation. For the demo, Flock showed a half-pipe event (see below). The player used a combination of joystick moves and button controls to perform various skateboarding tricks. Flock then attempted to show some of these moves with mixed success. He explained there were 12 different moves in this half-pipe event, and the player received points for the variety of their routine as well as possible bonus points at the end.

Cheifet asked if Skate or Die was available on other machines besides the C64. Flock said right now it was only available on the Commodore. It was designed on the C64 and took advantage of some of that machine’s unique features, including hardware sprites, the 16-color palette, and the three-voice sound chip. But EA was in the process of porting the game to other platforms.

Kildall asked about other events in Skate or Die besides the half-pipe. Flock said there was a total of five events. The half-pipe was modeled on real-world skateboarding. But there were also a couple of downhill events where the player could break bottles or skate through bushes or a drain pipe. The were also a “joust” event where you could play against three computer-controlled players that you had to whop with a little marine bopping stick.

Kildall asked about the price of Skate or Die. Flock said the suggested retail price was $29.95. Kildall wondered if there was something about the C64 market that you couldn’t generally charge more than $30 for games. Flock said that as the Commodore market got older, it became more price sensitive. There was a lot more product developed for the C64 than, say, the Amiga, where there were relatively few games available. Kildall wondered if EA might then start to de-emphasize the C64. Flock said no, the company made up for the low prices in volume.

Toy Saw Continued Growth for C64

For the next segment, Stewart Cheifet interviewed Max Toy, the new president of Commodore Business Machines, Inc., the North American division of Commodore International. Cheifet asked Toy if he really saw the C64 as a game machine. Toy said it would be real easy to say that. But what Commodore had seen in the marketplace was that the C64 was continuing to be used in business. It was being used for broader applications such as desktop publishing. It was being used in the small, tiny business market. And it was seeing a resurgence in the educational marketplace. So the C64 was much more than a “toy.” Toy acknowledged there had been a growth in the entertainment marketplace due to some of the software. But he insisted there was still new business software being written for the C64 as well.

Cheifet asked if the C64 was still a “current” machine. Were people still buying them? Toy said yes, the market continued to expand. Worldwide, Commodore sold between 1 million and 1.5 million C64s every year. There had been a new wave of young, first-time customers coming into the marketplace. In fact, Commodore probably welcomed more first-time computer users than any other company in the world. He added that the C64 was not old technology to the first-time user. It was new technology as far as they were concerned, and software developers continued to use the C64’s high-performance capabilities for a very high-value dollar.

Cheifet asked Toy what he considered the main competition for the C64 right now. Was it the lower-cost Apple or the Atari 520ST? Or was Commodore going up against video game console companies like Nintendo and Sega? (For some reason, Cheifet pronounced it “See-ga” rather than “Say-ga.”) Toy said it was all of the above. At the low end Commodore was competing against the game machines. But what they saw was parents deciding they wanted their child to have more than just a game machine. Those parents wanted to take the entertainment software further with education. At the other end of the spectrum, Commodore saw the C64 being used in television production environments.

Ultimately, Toy said the C64 remained an important part of Commodore’s business now and for the future. It was continuing to grow. So Commodore continued to spend research and development dollars adding peripherals and support capabilities to the product. He added that the passion of the Commodore users and what they had been able to do with the machines was absolutely incredible.

No Need for a Drummer with the C64

Bill Morrow, a Commodore user and professional musician from California, joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio for the final segment. Morrow had a bank of synthesizers hooked up to a C64. Kildall asked Morrow what made the C64 a good machine for a musician like himself. Morrow said first, it was inexpensive. Second, there was the sound interface device (SID) chip, which had three voices that could play individual notes separately or simultaneously. So for example, you could have a synthesized flute, bass, and violin all playing at the same time. Morrow could then study the attack, delay, sustain, and release of each note on the computer.

Cheifet asked Morrow to demonstrate a music program he used with the C64 called Master Composer. Morrow ran a sample composition and played it back using just the C64’s SID chip. (The song was “Celebration” by Kool & the Gang.) Morrow then conducted a second demo using three external synthesizer keyboards hooked up to the C64 via MIDI. With a drum machine and sound generator, this gave Morrow a total of 16 different tracks to work with. He used a program called Keyboard Controlled Sequencer by Dr. T’s Music Software to control the entire setup. Morrow then had the C64 perform an original song co-written by himself and James Anderson.

Cheifet asked Morrow about the “pleasure” of working with a machine like the C64. Morrow said the pleasure was he didn’t need a lot of musicians to rehearse with. Most of the time, he wore out other musicians with his demands to rehearse. But working with the C64, he didn’t need a drummer; the drum machine could just play all day long.

A Brief History of Commodore International

Max Toy would end up being one of seven individuals who oversaw Commodore International’s North American operations between the departure of Jack Tramiel in January 1984 and the company’s collapse in May 1994. Toy’s tenure only lasted about 18 months. And despite his on-air optimism about the future of the C64, it was the successive failure of Commodore’s North American branch to move its customer base beyond the entry-level computer that helped seal the company’s fate.

The Atlantic Acceptance Scandal and Irving Gould’s Takeover

Commodore was ultimately controlled by its chairman, Irving Gould, who also took over the CEO’s position in 1987. So how did he gain control of the company in the first place? Commodore International’s roots go back to around 1954, when Jack Tramiel and Manfred Kapp started their first business selling used and refurbished typewriters on consignment in New York City. The two men earned enough money to buy a Bronx-based business, the Singer Typewriter Company, and they later acquired an adding machine dealership.

Tramiel’s wife, Helen, had family living in Toronto, Ontario, and while on a visit to Canada, Jack found there was interest from local dealers in selling the adding machines. So Tramiel convinced the manufacturer, Everest, to give him the exclusive dealership rights for Canada, and in 1956, the Tramiels relocated to Toronto and established Everest Office Machine Company Limited. Kapp joined him shortly thereafter, and the partners and their wives started another business, Wholesale Typewriter Company, to sell used typewriters to the Canadian market.

In October 1958, the Tramiels and Kapps started yet another business, Commodore Portable Typewriter Company Limited, to import and distribute portable typewriters from Czechoslovakia. While Commodore quickly found buyers for their typewriters in Toronto’s two largest department stores, financing was a constant problem. Tramiel and Kapp had to fund their operation through accounts receivable factoring–i.e., selling their unpaid invoices for cash advances. But Tramiel was unhappy with the terms of their initial lender and decided to go looking for a better deal. Through an intermediary, he met Campbell Powell (C.P.) Morgan, the president of Atlantic Acceptance Limited.

Atlantic Acceptance was a financing company established by Morgan in 1953. Morgan was interested in expanding his operations into receivables factoring, and formed a new company, Commodore Sales Acceptance Limited (CSA), which would take over financing Tramiel and Kapp’s Commodore Portable Typewriter Company. In 1961, with Morgan’s backing, Tramiel and Kapp converted their privately held company into the publicly traded Commodore Business Machines (Canada) Limited. The proceeds of Commodore’s initial public offering largely serviced the debts owed to CSA and other entities controlled by Morgan. Morgan and several other Atlantic directors later joined Commodore’s board, with Morgan becoming chairman.

In Commodore’s first fiscal year as a public company, which ended in June 1962, it reported about $3.6 million in revenues and net income of just over $150,000. At this point, Commodore’s business was still selling typewriters and adding machines. In addition, the company opened two new subsidiaries to develop copying machines.

Over the next three years, Commodore grew rapidly, primarily through acquisitions and establishing more subsidiaries. By 1964, the company had more than doubled its net sales. And Tramiel was eager to keep growing. To that end, on April 7, 1965, the Commodore board held a meeting to approve Tramiel’s proposed acquisition of Willson Stationers & Envelopes Limited, Canada’s largest office supplies retailer, for approximately $3 million. During the meeting, Morgan and another Atlantic-affiliated director told Tramiel that they would make sure he had the funding to complete the deal. Two other Atlantic-affiliated directors cautioned Tramiel not to proceed with the acquisition but he ignored them.

On April 22, Commodore made a $100,000 deposit as a down payment on the Willson deal. But Morgan couldn’t make good on his promise to secure the rest of the funding. On June 3, the Commodore board held an emergency meeting, at which Tramiel requested approval to secure the $3 million he needed from another lender. One of the directors who opposed the deal advised Tramiel to walk away and forfeit the $100,000 deposit. Again,Tramiel refused. Eight days later, on June 11, the board met again and gave Tramiel the go-ahead to secure a six-month loan for the $3 million at 11-percent interest.

That same day, in an unrelated transaction, a Montreal investment bank made the last in a series of three-day short-term loans to Atlantic Acceptance for $5 million at 4.625-percent interest. The loan had to be repaid on Monday, June 14, 1965. Atlantic Acceptance sent the check on time. It bounced.

Defaulting on a $5 million note immediately sent Atlantic Acceptance into receivership. Tramiel had to move quickly to try and distance himself and Commodore from the resulting scandal. On June 22, the Commodore board held another meeting, at which time Morgan and the three other Atlantic-affiliated directors resigned. Tramiel and Kapp also took advantage of the opportunity and had the remaining five-member board (which included them) approve new five-year employment contracts for themselves with additional stock options.

Meanwhile, Tramiel was still determined to close the Willson Stationers deal. He and Kapp pledged 75,000 of their own shares in Atlantic Acceptance as collateral to their lender, Traders Realty. With the $3 million loan in hand, Commodore finally closed the purchase on June 23, 1965, the day after Atlantic Acceptance’s default.

With access to Morgan and Atlantic Access’ short-term funding cut off, however, Commodore had no way to pay back the $3 million owed to Traders when that note became due in six months. On top of that, the trustee that assumed control of Atlantic Acceptance was now starting to scrutinize all of Morgan’s dealings, including those involving Tramiel and Commodore over the past several years. Backed into a corner, Tramiel realized he had to sell Willson Stationers, the company he just spent the past three months trying to buy.

On August 10, 1965, the board met and approved Tramiel’s plan to sell Willson Stationers. The board also granted Tramiel and Kapp another round of stock options as “consideration” for them personally guaranteeing the Traders loan. Three days later, Tramiel and Kapp granted a Bahamas-based company , Amber Holdings Limited, the exclusive right to find a buyer for Willson. The deal was simple: Amber Holdings would keep any sales price in excess of $3 million as a commission.

Amber Holdings was created and controlled by–you guessed it–Irving Gould. Gould also owned a financing company, Jaypen Holdings Limited. Gould later recalled that he first met Tramiel sometime in July or August 1965 to discuss Commodore’s financial situation. Gould and Jaypen Holdings soon assumed Morgan and Atlantic Acceptance’s role as Commodore’s principal short-term financiers.

Gould found a buyer for Willson Stationers in November 1965, selling the company to U.S.-based Boise Cascade for $3,345,444. Traders got its $3 million. Amber Holdings and Gould got a $340,000 commission. Tramiel and Kapp received $20,000 in exchange for surrendering their stock options. The only losers were Commodore shareholders, as the company ended up losing about $600,000 on the entire Wilson Stationers adventure after factoring in the additional costs of the sale.

Commodore still had other financial problems to address as it unwound itself from Atlantic Acceptance. On November 8, 1965, Tramiel sent Gould a letter asking for further assistance with re-financing Commodore’s debts and potentially selling off additional assets. Tramiel also requested Gould delay Commodore’s obligation to repay an outstanding $325,000 loan owed to Jaypen Holdings. Gould eagerly obliged.

Throughout the first half of 1966, Gould executed a series of transactions on Commodore’s behalf that effectively made him the company’s controlling shareholder. The takeover became official on October 28, 1966, when Gould and one of his associates assumed two of Commodore’s five board seats. Gould also became chairman and de facto CEO, with Tramiel remaining as president.

In September 1969, Ontario Supreme Court Justice Sam Hughes issued an exhaustive report on the collapse of Atlantic Acceptance, which forms the basis for much of the narrative presented above. The Ontario government appointed Hughes as a Royal commissioner to conduct a formal inquiry in August 1965. During his four-year investigation, Hughes took sworn testimony from Tramiel, Kapp, and dozens of other witnesses. (Hughes only received limited testimony from C.P. Morgan, who died of leukemia in 1966.)

Hughes was not kind to Tramiel. With regard to Commodore, Hughes wrote, “The affairs of this company are still in the hands deeply imbrued with the pitch which originally defiled them in 1962, and into which they have been plunged again and again in succeeding years.” Hughes also didn’t have much confidence that things would improve under Irving Gould’s watch. The judge noted that Gould pleaded guilty to perjury in January 1960 after he lied to the Ontario Securities Commission during an investigation of his brother.

The CBM Coaching Carousel

Commodore’s 1967 annual report, reflecting Irving Gould’s first year as chairman, noted that the company “discontinued its main manufacturing program in Germany, and established a new one in Japan.” This preceded the company’s shift from manufacturing adding machines to electronic calculators in the 1970s. It was the calculator business that first brought Commodore into direct conflict with Texas Instruments, which launched its first price war in 1975. That conflict nearly destroyed Commodore, which reported a loss of nearly $3.8 million for the 1975 fiscal year.

In response, Gould and Jack Tramiel undertook a massive reorganization of the company. Commodore Business Machines (Canada) Limited became Commodore International Limited. The new Commodore was legally based in Gould’s favored offshore tax haven, the Bahamas, with corporate offices in New York City. Commodore International then created a Bahamian subsidiary, Commodore Electronics Limited, which actually held a bevy of subsidiary companies, including Commodore Business Machines, Inc. (CBM), the North American division personally overseen by Tramiel, who remained president of the entire Commodore International organization.

Another key subsidiary was MOS Technology, a Pennsylvania-based semiconductor manufacturer, which Commodore acquired in late 1976. Gould and Tramiel saw MOS as the key to achieving vertical integration in Commodore’s manufacturing, which would help protect it against future battles with rivals like Texas Instruments. Indeed, it was MOS Technology’s engineers who pushed Commodore into the computer market and developed the Commodore 64.

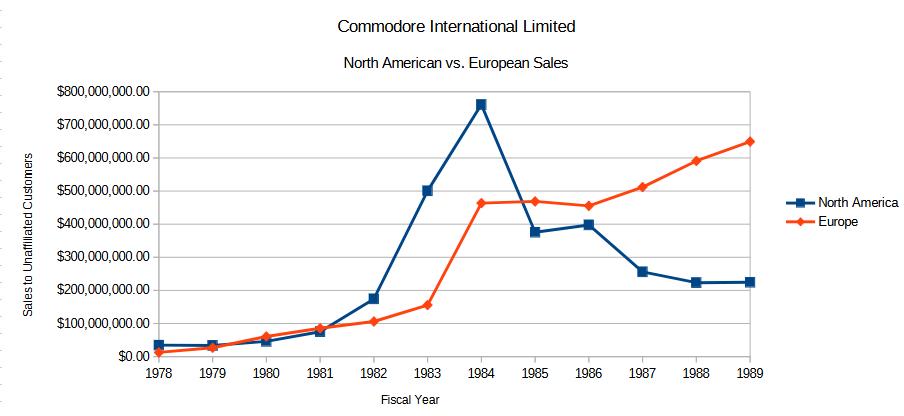

The early success of the C64, driven in large part by Tramiel’s aggressive price cutting, spurred Commodore to record sales levels in North America during 1983 and 1984. For the fiscal year ending June 30, 1983, Commodore reported just over $500 million in North American sales. The following year that figure climbed by more than 50 percent to $761.2 million. The 1984 fiscal year was also Commodore’s most profitable, with a reported net income of $143.8 million.

But following Tramiel’s departure in January 1984, Commodore’s U.S. sales took a steep nosedive and never recovered. The record profits of 1984 were soon followed by record losses in 1985 ($113.9 million) and 1986 ($127.9 million). This wasn’t just a matter of sales. Commodore was also seriously overleveraged. Irving Gould relied largely on issuing new debt to finance Commodore’s rapid expansion during the C64 boom. Don Greenbaum, Commodore’s corporate treasurer in this period, told friend of the blog Karl Kuras in a November 2021 interview that Gould refused to issue new stock for fear of diluting his own shares in the company. (Greenbaum added this was one of the main points of friction between Gould and Tramiel.) So even as Commodore managed to return to profitability at the end of its 1987 fiscal year, posting a net income of $28.6 million, it was still carrying about $370 million in debt.

The company might have collapsed by the time this Chronicles episode aired in 1988 had it not been for Commodore’s strong presence in Europe. Unlike the United States, where Commodore had become identified almost exclusively with the entry-level C64, the company remained a respected manufacturer of business computers throughout Europe, and in particular Germany. Perhaps the easiest way to illustrate the divide is with this chart, which shows the comparative North American (U.S. and Canada) and European sales of Commodore International between 1978 and 1989:

The sharp decline and leveling off of North American sales contributed to a vicious cycle of Gould hiring and firing multiple executives to oversee U.S. operations after Jack Tramiel’s departure. To use an American football analogy, Gould was the NFL owner whose team made an unexpected Super Bowl run. He then ran the popular head coach out of town and proceeded to hire and fire a series of lesser coaches who couldn’t replicate that one championship season.

The first rider on this coaching carousel was Marshall F. Smith, whom Gould appointed Commodore International’s new president and CEO immediately following Tramiel’s departure in January 1984. Smith was an experienced CEO, having spent the previous eight years running the U.S. division of Thyssen-Bornemisza, a Netherlands-based manufacturing conglomerate. He’d also done business with Gould before. In July 1978, Thyssen-Bornemisza purchased Interpool Ltd., a Bahamas-based shipping container company where Gould was chairman.

But Thyssen was not a fast-moving technology company. And Smith’s immediate priority was restructuring Commodore’s mounting debts and cutting expenses. In April 1985, Gould and Smith recruited another tech industry outsider, Thomas J. Rattigan, as president of Commodore Business Machines, putting him in charge of North American operations. Rattigan had been the president of PepsiCo Bottling International, where he built a reputation as a turnaround specialist in consumer products. Rattigan oversaw the launch of the Commodore 128 and the Amiga, two machines that were supposed to move Commodore beyond the C64.

At first, Gould seemed to be satisfied with his new management team’s progress. In November 1985, he elevated Smith to vice chairman and promoted Rattigan to president and chief operating officer of Commodore International. But then in March 1986, Gould decided to replace Smith as CEO with Rattigan. (Don Greenbaum told Karl Kuras that he’d prepared a report detailing how Smith had mismanaged Commodore’s inventory, which led to Gould firing Smith.) This move came shortly after Commodore reached a deal with its major lenders to extend their line of credit, which had been in default. Around this same time, Rattigan brought in a new general manager for North America, Nigel Shepherd, who had been successfully running Commodore’s Australia subsidiary.

Another year later, however, Gould decided that despite the fact Commodore had started turning a profit again, it was time to clean house. In April 1987, Gould abruptly fired Rattigan, Shepherd, and four other executives. Gould then assumed day-to-day control of Commodore International as CEO and named Alfred Duncan, the head of Commodore’s Canadian office, as general manager for U.S. operations.

The Rattigan firing proved costly. Contemporary news reports suggested that “personality conflicts” led to Gould’s rash decision and that he ordered security to personally escort Rattigan out of Commodore’s Pennsylvania offices without allowing him to retrieve his personal belongings. But Rattigan had signed a five-year employment contract, and Commodore still owed him $2 million in base salary plus additional benefits. Accordingly, Rattigan filed a $9 million breach of contract lawsuit in Manhattan federal court against Commodore. Gould responded in kind, with Commodore counter-suing Rattigan for $24 million, accusing him of “gross disregard” of his duties and ignoring Gould’s orders.

Rattigan ultimately prevailed. In February 1991, a jury ruled in his favor on the breach of contract claim. Gould then agreed to settle the case for $5 million rather than risk an even higher damages award from the judge. (Incidentally, the judge was Michael Mukasey, who later served as U.S. attorney general.)

For his part, Gould denied in an August 1987 interview with Andrea Knox of the Philadelphia Inquirer that personality conflict led to Rattigan’s dismissal. As Knox described it, “Gould had had enough of sitting on the sidelines and watching other people mismanage his company and rob him of hundreds of millions of dollars of net worth.” Indeed, Commodore’s stock–which Gould owned about 6 million of–had plummeted from a high of over $60 per share at the height of the C64 boom in 1983 to just $5 by the end of 1986.

And while Knox noted that Rattigan had managed to stem Commodore’s losses and turn a small profit, Gould felt this was due mostly to overly aggressive cost-cutting rather than growing North American sales. He specifically pointed to Rattigan cutting Commodore’s advertising budget, which Gould said was “greater than the reported profits in at least one quarter.”

A couple of months after Gould gave this interview, in October 1987, he appointed Max Toy as the new president of Commodore Business Machines. (I’m not entirely clear if he replaced Alfred Duncan or merely assumed a position on the organization chart above him.) Toy had been a senior vice president overseeing sales for XTRA 0Business Systems, a PC clone manufacturer owned by ITT Corporation. He’d also previously worked at IBM and Compaq. So not surprisingly, one of his top priorities after assuming the helm at CBM was to try and market a Commodore-branded PC compatible to the North American market. That was the Commodore Colt, a re-branded version of the company’s European Commodore PC 10-III.

But like all of Commodore’s efforts to break into North American PC compatible market, the Colt proved lame. Buffalo News columnist Lonnie Hudkins summed it up by saying the Colt, “arrived TOO late, is TOO expensive in comparison with the competition and offers TOO little excitement.” Elaborating further, Hudkins said CBM introduced the Colt at $899.95 (without a monitor), which was more than many dealers were charging for other existing PC clones.

So North American sales remained stagnant, dropping to $255.9 million and then flat-lining at $223.3 million in FY 1988 and $224.4 million in FY 1989. As you can probably guess, Gould wasn’t happy, and since he wouldn’t fire himself as CEO, he got rid of Toy instead. In April 1989, roughly 18 months after Toy joined the company, Gould replaced him with a new CBM president, Harold D. Copperman.

Copperman was another outside hire. He came from Apple, where he’d been general manager for east coast operations two years following a 20-year career at IBM. Coppeman joined Commodore a few weeks after Gould appointed a longtime ally and board member, Mehdi Ali, as Commodore International’s new president, filling a post that had been vacant since Rattigan’s firing. Gould remained CEO, but he was largely an absentee owner at this point, as he divided his time living in Toronto, New York City, and the Bahamas for tax reasons.

Speaking of living situations, Copperman told the Inquirer’s Valerie Reitman that he had no immediate plans to relocate his family from Connecticut to Pennsylvania, where CBM was based, because he wanted his youngest son to finish high school. Instead, Copperman said he commuted each day by piloting his private plane. (Gary Kildall would approve.)

Still, Copperman may have also been hedging his bets given recent history. He admitted to Reitman that some of his new employees “were wagering on how long he would last and holding mock contests to name all of his predecessors.” But his focus was on the future–and that was definitely not the C64. Instead, his focus was squarely on the Amiga.

That focus lasted until January 1991, when Gould fired Copperman and appointed James Dionne, Commodore’s Canadian sales manager and an 11-year company veteran, as CBM’s new president. Dionne lasted until October 1993, when Gould replaced him with Geoff Stliley. He left six months later–as the Commodore ship be sinking–to become head of sales and marketing for a data storage company.

As a postscript, Max Toy joined Ashton-Tate after his brief Commodore tenure. He eventually became that company’s vice president of sales and worldwide marketing. After Borland International acquired Ashton-Tate in 1991, Toy started a consulting firm and has since served as an executive and director for a number of startups in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was likely first broadcast in March 1988.

- Paul Schindler’s software review for this episode was the Electronic Encyclopedia (Grolier Electronic Publishing, $300).

- Lucy Morton never identified her C64 sweater design program by name. But I found a listing in a 1995 book, The Needlecrafter’s Computer Companion, for a program called Style & Chart 2.1 by Lucy Morton. This would appear to be a later revision of the original C64 program published by Cochenille Design Studio, which by then was also available for the Amiga and IBM PC for $90.

- Lewis “Kelly” Flock died in 2020 at the age of 67. Friend of the blog Ethan Johnson published a remembrance at his website, The History of How We Play. Kelly started at EA working in the warehouse before moving up the ranks into a junior production role on Skate or Die. He ended up leaving EA shortly thereafter to join Mediagenic (Activision), where he designed and produced a number of games before moving to Lucasarts. After a few more stops, Flock joined Sony in 1995, where he oversaw game development for the original PlayStation. Flock served as president of Sony Online Entertainment from 2000 to 2002 and later as executive vice president of video game publisher THQ from 2005 to 2007.

- Brian Dougherty’s tech career began at Mattel Electronics, where he designed games for the Mattel IntelliVision. In 1981, Dougherty left Mattel to co-found Imagic, a third-party developer of games for the IntelliVision and the Atari VCS (2600). When Atari’s parent company, Warner Communications, announced in December 1982 that its yearly earnings would be significantly lower than previously projected due to mounting losses at Atari, it derailed Imagic’s planned initial public offering scheduled for two days later. Not long thereafter, Imagic CEO Bill Grubb fired Dougherty after learning of his plans to start his own company, which became Berkeley Softworks. Dougherty took the company, later renamed GeoWorks Corporation, public in 1994. That same year, Dougherty launched Wink Communications, an interactive television company, which he sold to Liberty Media in 2002. Dougherty also co-founded GlobalPC, a company that marketed cheap Internet-ready computers based on GEOS. He sold that company to MyTurn.com, which filed for bankruptcy in 2001. After that, Dougherty started a new software development company, Airset, Inc., which closed in 2015.

- Berkeley Softworks released the initial version of GEOS for the Commodore 64 in 1986. Later releases supported the Commodore 128 and the Apple II. In 1990, the now-GeoWorks Corporation released a 16-bit GEOS for MS-DOS computers called PC/GEOS. GeoWorks later created a form of PC/GEOS for personal digital assistants, PEN/GEOS. The subsequent fate of GEOS and its many incarnations is beyond the scope of this exceptionally long blog post, so for now I’ll recommend you read Ernie Smith’s account at Tedium.

- Skate or Die is notable as the first game internally developed at Electronic Arts as opposed to by an outside programmer or developer working under contract. EA later published Skate or Die for the Apple IIgs, Amstrad CPC, and MS-DOS platforms. Konami also ported and released a version for the Nintendo Entertainment System under license from EA, which at this time refused to publish on video game consoles.

- Like many computer products, the KoalaPad started out as a project developed at Xerox PARC that Xerox decided not to commercially develop. David Thornburg of PARC created the initial touchpad tablet prototype in the early 1970s. Thornburg left PARC in 1981 and Xerox let him take his invention with him. Shortly thereafter, Thornburg joined a former PARC colleague, George White, who started his own company–initially called Icontrol Inc., but later renamed Koala Technologies Corporation–to develop computer mice. In a 2017 interview with Kay Savetz for ANTIC: The Atari 8-Bit Podcast, White said his venture capital backers were more interested in the touchpad technology than mice. (Savetz separately interviewed David Thornburg around the same time.) So the company released the first KoalaPad for the Apple II in May 1983, with subsequent versions made for the Commodore 64 and other platforms. In 1986, Pentron Corporation acquired Koala Technologies and assumed its name. But in 1989, the new Koala sold off most of its businesses except for a plastics molding company and subsequently adopted the name Rotonics Manufacturing.

- Paul Kleinmeyer wrote Master Composer, which Utah-based Access Software published in 1983. According to Michael Quigely’s review of the program for the December 1984 issue of RUN, one of the included sample pieces was Donna Summer’s “She Works Hard for the Money.”

- Emile Tobenfield is the “Dr. T” behind Dr. T’s Music Software, although his doctorate is in physics rather than music. Tobenfield started working with synthesizers in the late 1970s before developing his first MIDI sequencer for the Commodore 64 in 1984. He incorporated Dr. T’s Music Software, Inc., in Massachusetts in 1988. The Keyboard Controlled Sequencer later evolved into a multi-tasking music package for the Atari ST line called Omega II. Tobenfield left Dr. T’s Music Software in 1993, citing “a severe case of burn-out” and lack of interest in the company’s direction. As best I can tell, the company went out of business the following year.

- This episode may have been the first national television appearance of Tetris in the United States. Obviously, the history of Tetris would require its own blog post. For now, go watch Norman Caruso’s 2019 documentary on “The Story of Tetris” at The Gaming Historian.